Fillable Printable Title Page For Apa

Fillable Printable Title Page For Apa

Title Page For Apa

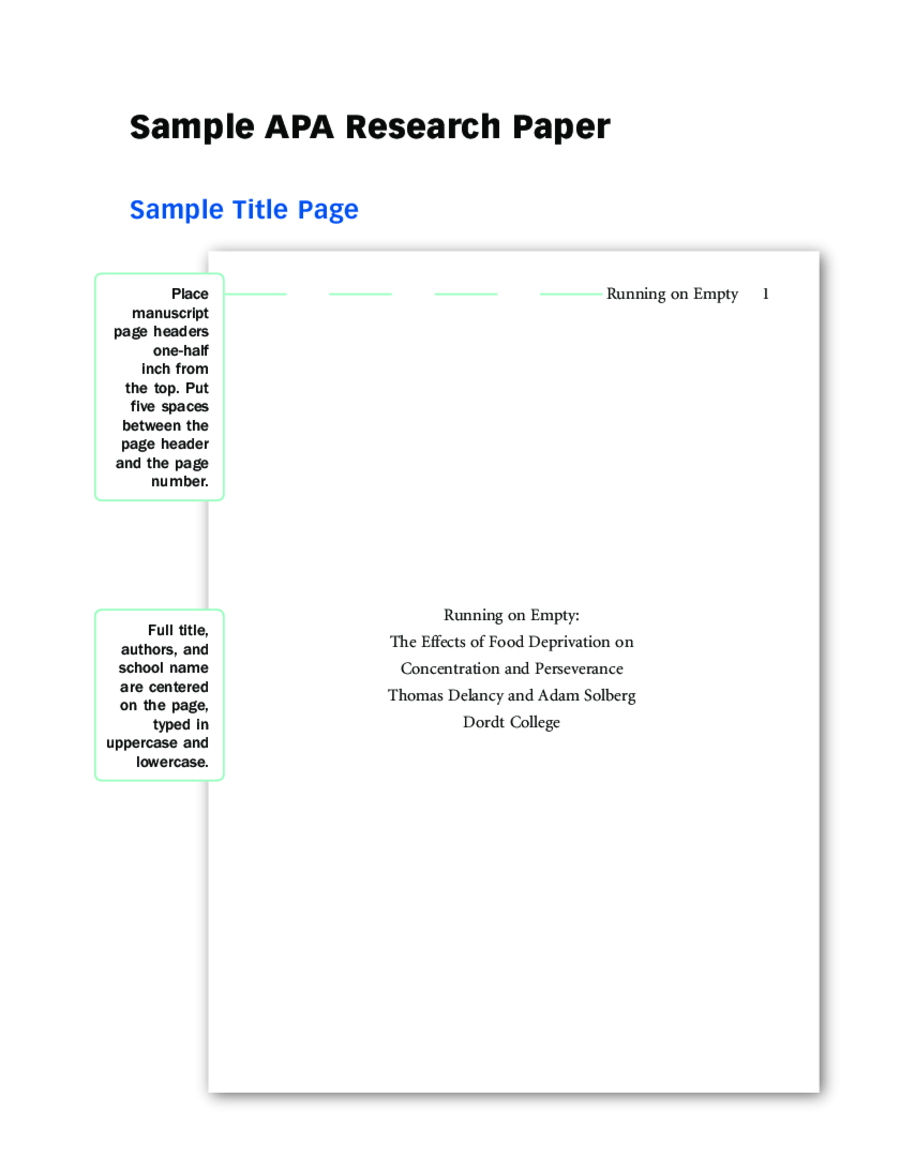

Sample APA Research Paper

Sample Title Page

Running on Empty 1

Running on Empty:

The Effects of Food Deprivation on

Concentration and Perseverance

Thomas Delancy and Adam Solberg

Dordt College

Place

manuscript

page headers

one-half

inch from

the top. Put

five spaces

between the

page header

and the page

number.

Full title,

authors, and

school name

are centered

on the page,

typed in

uppercase and

lowercase.

34

The abstract

summarizes

the problem,

participants,

hypotheses,

methods

used,

results, and

conclusions.

Sample Abstract

Running on Empty 2

Abstract

This study examined the effects of short-term food deprivation on two

cognitive abilities—concentration and perseverance. Undergraduate

students (N-51) were tested on both a concentration task and a

perseverance task after one of three levels of food deprivation: none, 12

hours, or 24 hours. We predicted that food deprivation would impair both

concentration scores and perseverance time. Food deprivation had no

significant effect on concentration scores, which is consistent with recent

research on the effects of food deprivation (Green et al., 1995; Green

et al., 1997). However, participants in the 12-hour deprivation group

spent significantly less time on the perseverance task than those in both

the control and 24-hour deprivation groups, suggesting that short-term

deprivation may affect some aspects of cognition and not others.

An APA Research Paper Model

Thomas Delancy and Adam Solberg wrote the following research paper for

a psychology class. As you review their paper, read the side notes and examine the

following:

● The use and documentation of their numerous sources.

● The background they provide before getting into their own study results.

● The scientific language used when reporting their results.

The

introduction

states the

topic and

the main

questions to

be explored.

The

researchers

supply

background

information

by discussing

past research

on the topic.

Extensive

referencing

establishes

support

for the

discussion.

Running on Empty 3

Running on Empty: The Effects of Food Deprivation

on Concentration and Perseverance

Many things interrupt people’s ability to focus on a task: distractions,

headaches, noisy environments, and even psychological disorders. To

some extent, people can control the environmental factors that make it

difficult to focus. However, what about internal factors, such as an empty

stomach? Can people increase their ability to focus simply by eating

regularly?

One theory that prompted research on how food intake affects the

average person was the glucostatic theory. Several researchers in the

1940s and 1950s suggested that the brain regulates food intake in order

to maintain a blood-glucose set point. The idea was that people become

hungry when their blood-glucose levels drop significantly below their set

point and that they become satisfied after eating, when their blood-glucose

levels return to that set point. This theory seemed logical because glucose

is the brain’s primary fuel (Pinel, 2000). The earliest investigation of the

general effects of food deprivation found that long-term food deprivation

(36 hours and longer) was associated with sluggishness, depression,

irritability, reduced heart rate, and inability to concentrate (Keys, Brozek,

Henschel, Mickelsen, & Taylor, 1950). Another study found that fasting

for several days produced muscular weakness, irritability, and apathy or

depression (Kollar, Slater, Palmer, Docter, & Mandell, 1964). Since that time,

research has focused mainly on how nutrition affects cognition. However, as

Green, Elliman, and Rogers (1995) point out, the effects of food deprivation

on cognition have received comparatively less attention in recent years.

Center the

title one inch

from the top.

Double-space

throughout.

Running on Empty 4

The relatively sparse research on food deprivation has left room for

further research. First, much of the research has focused either on chronic

starvation at one end of the continuum or on missing a single meal at the

other end (Green et al., 1995). Second, some of the findings have been

contradictory. One study found that skipping breakfast impairs certain

aspects of cognition, such as problem-solving abilities (Pollitt, Lewis,

Garza, & Shulman, 1983). However, other research by M. W. Green, N.

A. Elliman, and P. J. Rogers (1995, 1997) has found that food deprivation

ranging from missing a single meal to 24 hours without eating does not

significantly impair cognition. Third, not all groups of people have been

sufficiently studied. Studies have been done on 9–11 year-olds (Pollitt et

al., 1983), obese subjects (Crumpton, Wine, & Drenick, 1966), college-age

men and women (Green et al., 1995, 1996, 1997), and middle-age males

(Kollar et al., 1964). Fourth, not all cognitive aspects have been studied.

In 1995 Green, Elliman, and Rogers studied sustained attention, simple

reaction time, and immediate memory; in 1996 they studied attentional

bias; and in 1997 they studied simple reaction time, two-finger tapping,

recognition memory, and free recall. In 1983, another study focused on

reaction time and accuracy, intelligence quotient, and problem solving

(Pollitt et al.).

According to some researchers, most of the results so far indicate that

cognitive function is not affected significantly by short-term fasting (Green

et al., 1995, p. 246). However, this conclusion seems premature due to the

relative lack of research on cognitive functions such as concentration and

perseverance. To date, no study has tested perseverance, despite its

importance in cognitive functioning. In fact, perseverance may be a better

indicator than achievement tests in assessing growth in learning and

thinking abilities, as perseverance helps in solving complex problems

(Costa, 1984). Another study also recognized that perseverance, better

learning techniques, and effort are cognitions worth studying (D’Agostino,

1996). Testing as many aspects of cognition as possible is key because the

nature of the task is important when interpreting the link between food

deprivation and cognitive performance (Smith & Kendrick, 1992).

Clear

transitions

guide readers

through the

researchers’

reasoning.

The

researchers

explain how

their study

will add to

past research

on the topic.

The

researchers

support their

decision to

focus on

concentration

and

perseverance.

Running on Empty 5

Therefore, the current study helps us understand how short-term food

deprivation affects concentration on and perseverance with a difficult task.

Specifically, participants deprived of food for 24 hours were expected to

perform worse on a concentration test and a perseverance task than those

deprived for 12 hours, who in turn were predicted to perform worse than

those who were not deprived of food.

Method

Participants

Participants included 51 undergraduate-student volunteers (32

females, 19 males), some of whom received a small amount of extra credit

in a college course. The mean college grade point average (GPA) was 3.19.

Potential participants were excluded if they were dieting, menstruating,

or taking special medication. Those who were struggling with or had

struggled with an eating disorder were excluded, as were potential

participants addicted to nicotine or caffeine.

Materials

Concentration speed and accuracy were measured using an online

numbers-matching test (www.psychtests.com/tests/iq/concentration.html)

that consisted of 26 lines of 25 numbers each. In 6 minutes, participants

were required to find pairs of numbers in each line that added up to 10.

Scores were calculated as the percentage of correctly identified pairs out of

a possible 120. Perseverance was measured with a puzzle that contained

five octagons—each of which included a stencil of a specific object (such

as an animal or a flower). The octagons were to be placed on top of

each other in a specific way to make the silhouette of a rabbit. However,

three of the shapes were slightly altered so that the task was impossible.

Perseverance scores were calculated as the number of minutes that a

participant spent on the puzzle task before giving up.

Procedure

At an initial meeting, participants gave informed consent. Each

consent form contained an assigned identification number and requested

the participant’s GPA. Students were then informed that they would be

notified by e-mail and telephone about their assignment to one of the

The

researchers

state their

initial

hypotheses.

Headings and

subheadings

show the

paper’s

organization.

The

experiment’s

method is

described,

using the

terms and

acronyms of

the discipline.

Passive voice

is used to

emphasize

the

experiment,

not the

researchers;

otherwise,

active voice

is used.

Running on Empty 6

three experimental groups. Next, students were given an instruction

sheet. These written instructions, which we also read aloud, explained

the experimental conditions, clarified guidelines for the food deprivation

period, and specified the time and location of testing.

Participants were randomly assigned to one of these conditions

using a matched-triplets design based on the GPAs collected at the

initial meeting. This design was used to control individual differences

in cognitive ability. Two days after the initial meeting, participants were

informed of their group assignment and its condition and reminded that,

if they were in a food-deprived group, they should not eat anything after

10 a.m. the next day. Participants from the control group were tested at

7:30 p.m. in a designated computer lab on the day the deprivation started.

Those in the 12-hour group were tested at 10 p.m. on that same day.

Those in the 24-hour group were tested at 10:40 a.m. on the following day.

At their assigned time, participants arrived at a computer lab

for testing. Each participant was given written testing instructions,

which were also read aloud. The online concentration test had already

been loaded on the computers for participants before they arrived for

testing, so shortly after they arrived they proceeded to complete the

test. Immediately after all participants had completed the test and their

scores were recorded, participants were each given the silhouette puzzle

and instructed how to proceed. In addition, they were told that (1) they

would have an unlimited amount of time to complete the task, and (2)

they were not to tell any other participant whether they had completed

the puzzle or simply given up. This procedure was followed to prevent

the group influence of some participants seeing others give up. Any

participant still working on the puzzle after 40 minutes was stopped to

keep the time of the study manageable. Immediately after each participant

stopped working on the puzzle, he/she gave demographic information

and completed a few manipulation-check items. We then debriefed and

dismissed each participant outside of the lab.

Attention is

shown to

the control

features.

The

experiment is

laid out step

by step,

with time

transitions

like “then”

and “next.”

Running on Empty 7

Results

Perseverance data from one control-group participant were

eliminated because she had to leave the session early. Concentration data

from another control-group participant were dropped because he did not

complete the test correctly. Three manipulation-check questions indicated

that each participant correctly perceived his or her deprivation condition

and had followed the rules for it. The average concentration score was

77.78 (SD = 14.21), which was very good considering that anything over

50 percent is labeled “good” or “above average.” The average time spent

on the puzzle was 24.00 minutes (SD = 10.16), with a maximum of 40

minutes allowed.

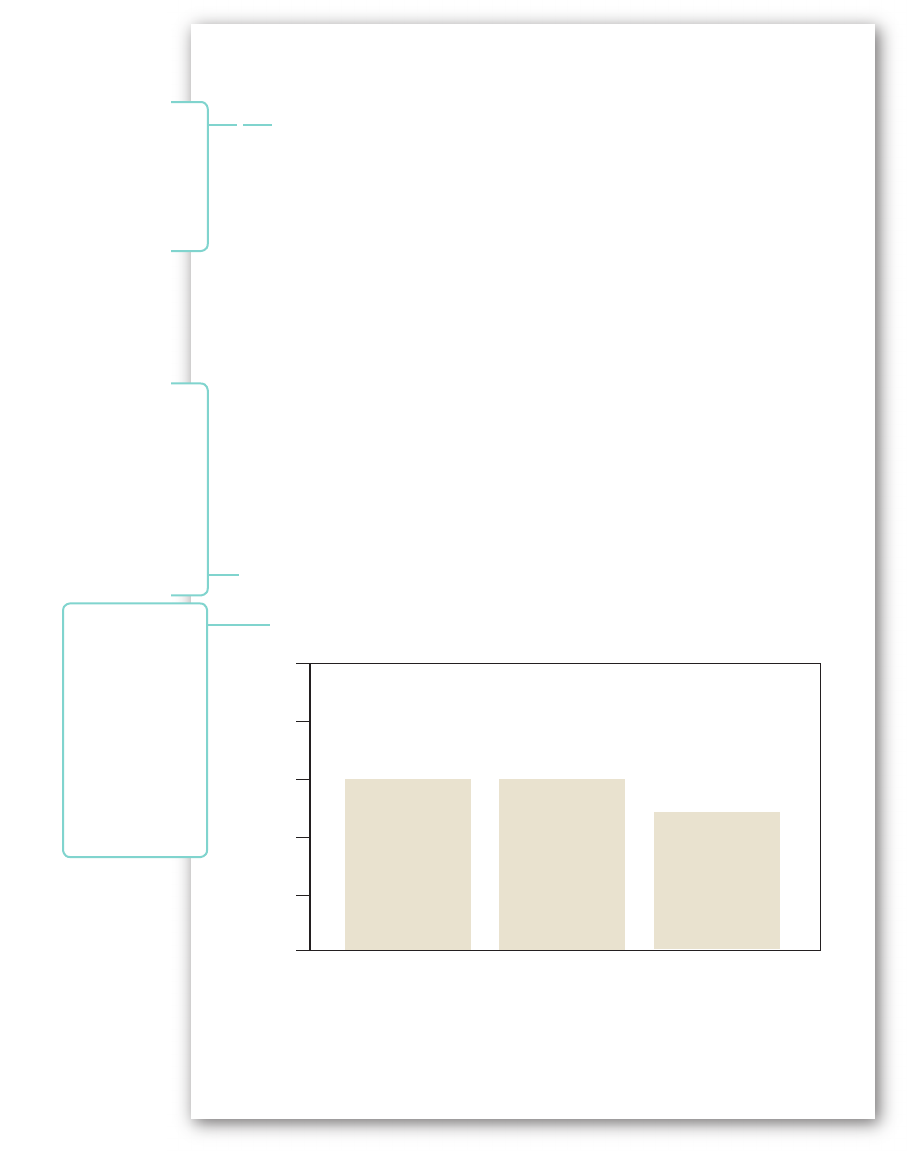

We predicted that participants in the 24-hour deprivation group

would perform worse on the concentration test and the perseverance task

than those in the 12-hour group, who in turn would perform worse than

those in the control group. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA)

showed no significant effect of deprivation condition on concentration,

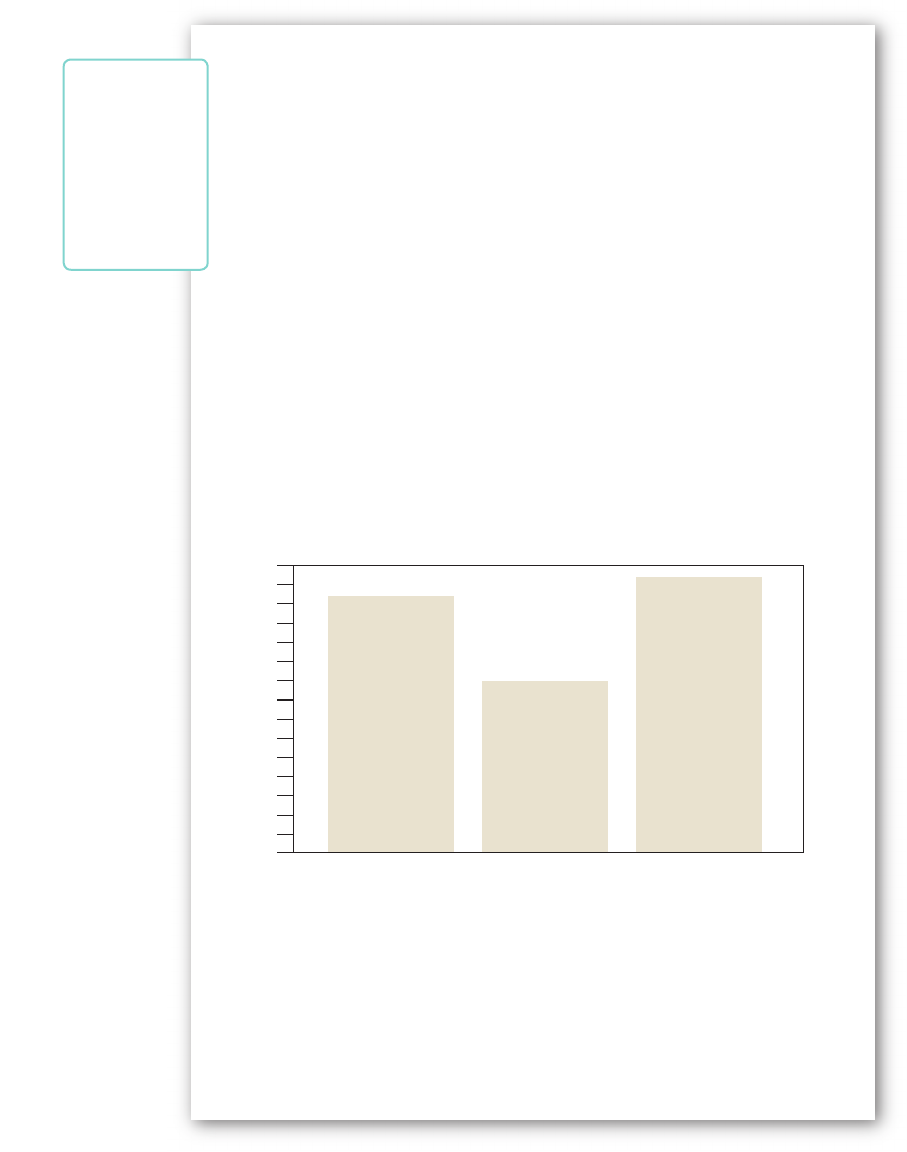

F(2,46) = 1.06, p = .36 (see Figure 1). Another one-way ANOVA indicated

Figure 1.

No deprivation 12-hour deprivation 24-hour deprivation

Deprivation Condition

100

90

80

70

60

50

Mean score on concentration test

The writers

summarize

their findings,

including

problems

encountered.

“See Figure

1” sends

readers to a

figure (graph,

photograph,

chart, or

drawing)

contained in

the paper.

All figures

and

illustrations

(other than

tables) are

numbered

in the order

that they

are first

mentioned in

the text.

Running on Empty 8

a significant effect of deprivation condition on perseverance time,

F(2,47) = 7.41, p < .05. Post-hoc Tukey tests indicated that the 12-hour

deprivation group (M = 17.79, SD = 7.84) spent significantly less time

on the perseverance task than either the control group (M = 26.80, SD =

6.20) or the 24-hour group (M = 28.75, SD = 12.11), with no significant

difference between the latter two groups (see Figure 2). No significant

effect was found for gender either generally or with specific deprivation

conditions, Fs < 1.00. Unexpectedly, food deprivation had no significant

effect on concentration scores. Overall, we found support for our

hypothesis that 12 hours of food deprivation would significantly impair

perseverance when compared to no deprivation. Unexpectedly, 24 hours

of food deprivation did not significantly affect perseverance relative to the

control group. Also unexpectedly, food deprivation did not significantly

affect concentration scores.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to test how different levels of food

deprivation affect concentration on and perseverance with difficult tasks.

30

28

26

24

22

20

18

16

14

12

10

8

6

4

2

0

Mean score on perseverance test

Figure 2.

No deprivation 12-hour deprivation 24-hour deprivation

Deprivation Condition

The

researchers

restate their

hypotheses

and the

results, and

go on to

interpret

those results.

Running on Empty 9

We predicted that the longer people had been deprived of food, the lower

they would score on the concentration task, and the less time they would

spend on the perseverance task. In this study, those deprived of food did

give up more quickly on the puzzle, but only in the 12-hour group. Thus,

the hypothesis was partially supported for the perseverance task. However,

concentration was found to be unaffected by food deprivation, and thus

the hypothesis was not supported for that task.

The findings of this study are consistent with those of Green et al.

(1995), where short-term food deprivation did not affect some aspects

of cognition, including attentional focus. Taken together, these findings

suggest that concentration is not significantly impaired by short-term

food deprivation. The findings on perseverance, however, are not as easily

explained. We surmise that the participants in the 12-hour group gave up

more quickly on the perseverance task because of their hunger produced

by the food deprivation. But why, then, did those in the 24-hour group

fail to yield the same effect? We postulate that this result can be explained

by the concept of “learned industriousness,” wherein participants who

perform one difficult task do better on a subsequent task than the

participants who never took the initial task (Eisenberger & Leonard,

1980; Hickman, Stromme, & Lippman, 1998). Because participants

had successfully completed 24 hours of fasting already, their tendency

to persevere had already been increased, if only temporarily. Another

possible explanation is that the motivational state of a participant may be

a significant determinant of behavior under testing (Saugstad, 1967). This

idea may also explain the short perseverance times in the 12-hour group:

because these participants took the tests at 10 p.m., a prime time of the

night for conducting business and socializing on a college campus, they

may have been less motivated to take the time to work on the puzzle.

Research on food deprivation and cognition could continue in several

directions. First, other aspects of cognition may be affected by short-term

food deprivation, such as reading comprehension or motivation. With

respect to this latter topic, some students in this study reported decreased

motivation to complete the tasks because of a desire to eat immediately

The writers

speculate

on possible

explanations

for the

unexpected

results.

Running on Empty 10

after the testing. In addition, the time of day when the respective groups

took the tests may have influenced the results: those in the 24-hour

group took the tests in the morning and may have been fresher and more

relaxed than those in the 12-hour group, who took the tests at night.

Perhaps, then, the motivation level of food-deprived participants could

be effectively tested. Second, longer-term food deprivation periods, such

as those experienced by people fasting for religious reasons, could be

explored. It is possible that cognitive function fluctuates over the duration

of deprivation. Studies could ask how long a person can remain focused

despite a lack of nutrition. Third, and perhaps most fascinating, studies

could explore how food deprivation affects learned industriousness. As

stated above, one possible explanation for the better perseverance times

in the 24-hour group could be that they spontaneously improved their

perseverance faculties by simply forcing themselves not to eat for 24

hours. Therefore, research could study how food deprivation affects the

acquisition of perseverance.

In conclusion, the results of this study provide some fascinating

insights into the cognitive and physiological effects of skipping meals.

Contrary to what we predicted, a person may indeed be very capable of

concentrating after not eating for many hours. On the other hand, if one

is taking a long test or working long hours at a tedious task that requires

perseverance, one may be hindered by not eating for a short time, as

shown by the 12-hour group’s performance on the perseverance task.

Many people—students, working mothers, and those interested in fasting,

to mention a few—have to deal with short-term food deprivation,

intentional or unintentional. This research and other research to follow

will contribute to knowledge of the disadvantages—and possible

advantages—of skipping meals. The mixed results of this study suggest

that we have much more to learn about short-term food deprivation.

The

conclusion

summarizes

the

outcomes,

stresses the

experiment’s

value, and

anticipates

further

advances on

the topic.

Running on Empty 11

References

Costa, A. L. (1984). Thinking: How do we know students are getting better

at it? Roeper Review, 6, 197–199.

Crumpton, E., Wine, D. B., & Drenick, E. J. (1966). Starvation: Stress

or satisfaction? Journal of the American Medical Association, 196,

394–396.

D’Agostino, C. A. F. (1996). Testing a social-cognitive model of

achievement motivation.-Dissertation Abstracts International Section

A: Humanities & Social Sciences, 57, 1985.

Eisenberger, R., & Leonard, J. M. (1980). Effects of conceptual task

difficulty on generalized persistence. American Journal of Psychology,

93, 285–298.

Green, M. W., Elliman, N. A., & Rogers, P. J. (1995). Lack of effect of

short-term fasting on cognitive function. Journal of Psychiatric

Research, 29, 245–253.

Green, M. W., Elliman, N. A., & Rogers, P. J. (1996). Hunger, caloric

preloading, and the selective processing of food and body shape

words. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 35, 143–151.

Green, M. W., Elliman, N. A., & Rogers, P. J. (1997). The study effects of

food deprivation and incentive motivation on blood glucose levels

and cognitive function. Psychopharmacology, 134, 88–94.

Hickman, K. L., Stromme, C., & Lippman, L. G. (1998). Learned

industriousness: Replication in principle. Journal of General

Psychology, 125, 213–217.

Keys, A., Brozek, J., Henschel, A., Mickelsen, O., & Taylor, H. L. (1950).

The biology of human starvation (Vol. 2). Minneapolis: University of

Minnesota Press.

Kollar, E. J., Slater, G. R., Palmer, J. O., Docter, R. F., & Mandell, A. J.

(1964). Measurement of stress in fasting man. Archives of General

Psychology, 11, 113–125.

Pinel, J. P. (2000). Biopsychology (4th ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

All works

referred to

in the paper

appear on

the reference

page, listed

alphabetically

by author

(or title).

Each entry

follows APA

guidelines

for listing

authors,

dates,

titles, and

publishing

information.

Capitalization,

punctuation,

and hanging

indentation

are consistent

with APA

format.