Fillable Printable Detailed Risk Management Form

Fillable Printable Detailed Risk Management Form

Detailed Risk Management Form

i

FM 100-14

Field Manual Headquarters

No. 100- 14 Department of the Army

Washington, DC, 23 April 1998

Risk Management

Contents

Page

Preface

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ii

Introduction

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

iii

Chapter 1 Risk Management Fundamentals

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1-1

Background . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1-2

Principles. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1-3

Applicability . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1-4

Constraints . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1-7

Chapter 2 Risk Management Process

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2-0

The Five Steps: An Overview . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2-0

The Five Steps Applied . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2-2

Tools and Pitfalls . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2-19

Chapter 3 Risk Management Implementation

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

3-0

Moral and Ethical Implications for Leaders . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .3-0

Responsibilities . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3-1

Integration into Training and Operations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3-7

Assessment of the Risk Management Process. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3-9

Appendix Examples of Risk Management Application

. . . . . . . Appendix-1

Glossary

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Glossary-0

References

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

References-0

Index

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Index-1

DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION:

Approved for public release; distribution is

unlimited.

ii

Preface

FM 100-14 applies across the wide range of Army operations. It

explains the principles, procedures, and responsibilities to

successfully apply the

risk management process

to conserve combat

power and resources. The manual applies to both Army and civilian

personnel during all Army activities, including joint, multinational,

and interagency environments.

The manual is intended to help commanders,

1

their staffs,

leaders,

2

and managers develop a framework to make risk

management a routine part of planning

,

preparing

,

and executing

operational missions and everyday tasks. This framework will allow

soldiers to operate with maximum initiative, flexibility, and

adaptability. Although the manual’s prime focus is the operational

Army, the principles of risk management apply to all Army activities.

Army operations—especially combat operations—are demanding

and complex. They are inherently dangerous, including tough,

realistic training. Managing risks related to such operations requires

educated judgment and professional competence. The risk

management pr ocess allows individuals to make informed, conscious

decisions to accept risks at acceptable levels.

This manual is not a substitute for thought. Simply r eading it will

not make one adept in building protection around a mission.

3

Soldiers

should compare the doctrine herein against their own experience and

think about why, when, and how it

applies to their situation and area

of responsibility. If the doctrine herein is to be useful, it must become

second nature.

The proponent of this manual is HQ TRADOC. Send comments

and recommendations on DA Form 2028 directly to Commander, US

Army Training and Doctrine Command, ATTN: ATBO-SO, Fort

Monroe, VA 23651-5000.

Unless this publication states otherwise, masculine nouns and

pronouns do not refer exclusively to men.

1

The term

commander

as used herein refers to personnel in a command

position.

2

The term

leader

as used herein refers to commanders, personnel in the

chain of command (team, squad, section, platoon leader), and staff mem-

bers having personnel supervisory responsibility.

3

The term

mission

as used herein includes mission, operation, or task.

iii

Introduction

Risk management is not an add-on feature to the decision-

making process but rather a fully integrated element of

planning and executing operations... Risk management helps

us pr eserve combat power and retain the flexibility for bold and

decisive action. Proper risk management is a combat multiplier

that we can ill afford to squander.

General Dennis J. Reimer

Chief of Staff, Army

27 July 1995

The Army’s fundamental purpose is to fight and win the nation’s

wars. For this purpose, the country gives the Army critical resources,

including those most valuable—its sons and daughters. The Army

uses its resources to generate overwhelming combat power to fight

and win quickly, decisively, and with minimal losses. The Army’s

inherent responsibility to the nation is to protect and preserve its

resources—a responsibility that resides at all levels. Risk management

is an effective process for preserving resources. It is not an event. It

is both an art and a science. Soldiers use it to identify tactical and

accident risks, which they reduce by avoiding, controlling, or

eliminating hazards.

The Army introduced the risk management process into training,

the operational environments, and materiel acquisition in the late

1980s. Risk management was originally perceived as solely a safety

officer function. However, by the early 1990s, the Army established a

goal to integrate risk management into all Army processes and

activities and into every individual’s behavior, both on and off duty.

Since the process was introduced, the personal involvement of

commanders in pr eventing accidents—and their aggr essive use of the

process—have become driving factors in the steady downward trend

in Army accidental losses.

Leaders must understand the importance of the process in

conserving combat power and resources. Risk management, like

reconnaissance and security, is an ongoing process that continues from

mission to mission. Within the mission, leaders must know when the

process begins and who has responsibility. It must be integral to the

military decision. The process is an important means to enhance

situational awareness.

Risk Management

iv

Risk decisions are commanders’ business. Such decisions are

normally based on the next higher commander ’s guidance on how

much risk he is willing to accept and delegate for the mission. Risk

decisions should be made at the lowest possible level, except in

extreme circumstances. Training operations, including those at

combat training centers (CTCs), may be of such intensity that risk

decision are retained at a higher level.

Both leaders and staffs manage risk. Staff members continuously

look for hazards associated with their areas of expertise. They then

recommend controls to reduce risks. Hazards and the resulting risks

may vary as circumstances change and experience is gained. Leaders

and individual soldiers become the assessors for ever-changing

hazards such as those associated with environment (weather;

visibility; contaminated air, water, and soil), equipment readiness,

individual and unit experience, and fatigue. Leaders should advise

the chain of command on risks and risk reduction measures.

1-1

Chapter 1

Risk Management Fundamentals

Sizing up opponents to determine victory, assessing dangers

and distances is the pr oper course of action for military leaders.

Sun Tzu, The Art of War , “Terrain”

Risk management

is the process of identifying, assessing,

and controlling risks arising from operational factors

and making decisions that balance risk costs with

mission benefits. Leaders and soldiers at all levels use

risk management. It applies to all missions and

environments across the wide range of Army

operations. Risk management is fundamental in

developing confident and competent leaders and units.

Proficiency in applying risk management is critical to

conserving combat power and resources. Commanders

must firmly ground current and future leaders in the

critical skills of the five-step risk management process.

Risk is characterized by both the probability and severity

of a potential loss that may r esult fr om hazards due to the

presence of an enemy, an adversary, or some other

hazardous condition. Perception of risk varies from

person to person. What is risky or dangerous to one

person may not be to another. Perception influences

leaders’ decisions. A publicized event such as a training

accident or a relatively minor incident may increase the

public’s perception of risk for that particular event and

time—sometimes to the point of making such risks

unacceptable. Failure to effectively manage the risk

may make an operation too costly—politically,

economically, and in terms of combat power (soldiers

lives and equipment). This chapter presents the

background, principles, applicability, and

constraints

relating to the

risk management process.

Risk Management

1-2

Army

World War II

1942–1945

Korea

1950–1953

Vietnam

1965–1972

Desert Shield/

Storm

1

1990–1991

Accidents

Friendly Fire

Enemy Action

56%

1%

43%

44%

1%

55%

54%

1%

45%

75%

5%

20%

1

These numbers include the relatively long buildup time and short

period of combat action

BACKGROUND

Throughout the history of armed conflict, government and

military leaders have tried to reckon with the effect of casualties on

policy, strategy, and mission accomplishment. Government and

military leaders consider battle losses from different perspectives.

However, both must balance the following against the value of

national objectives:

• Effects of casualties.

• Impact on civilians.

• Damage to the environment.

• Loss of equipment.

• Level of public reaction.

War is inherently complex, dynamic, and fluid. It is characterized

by uncertainty, ambiguity, and friction.

Uncertainty

results from

unknowns or lack of information.

Ambiguity

is the blurring or fog that

makes it difficult to distinguish fact from impression about a situation

and the enemy.

Friction

results from change, operational hazards,

fatigue, and fears br ought on by danger. These characteristics cloud the

operating environment; they create risks that af fect an army’s ability to

fight and win. In uncertainty, ambiguity, and friction, both danger and

opportunity exist. Hence, a leader’s ability to adapt and take risks are

key traits. Chapter 2 of FM 100-5 provides information on the

challenging cir cumstances of military operations during conflict.

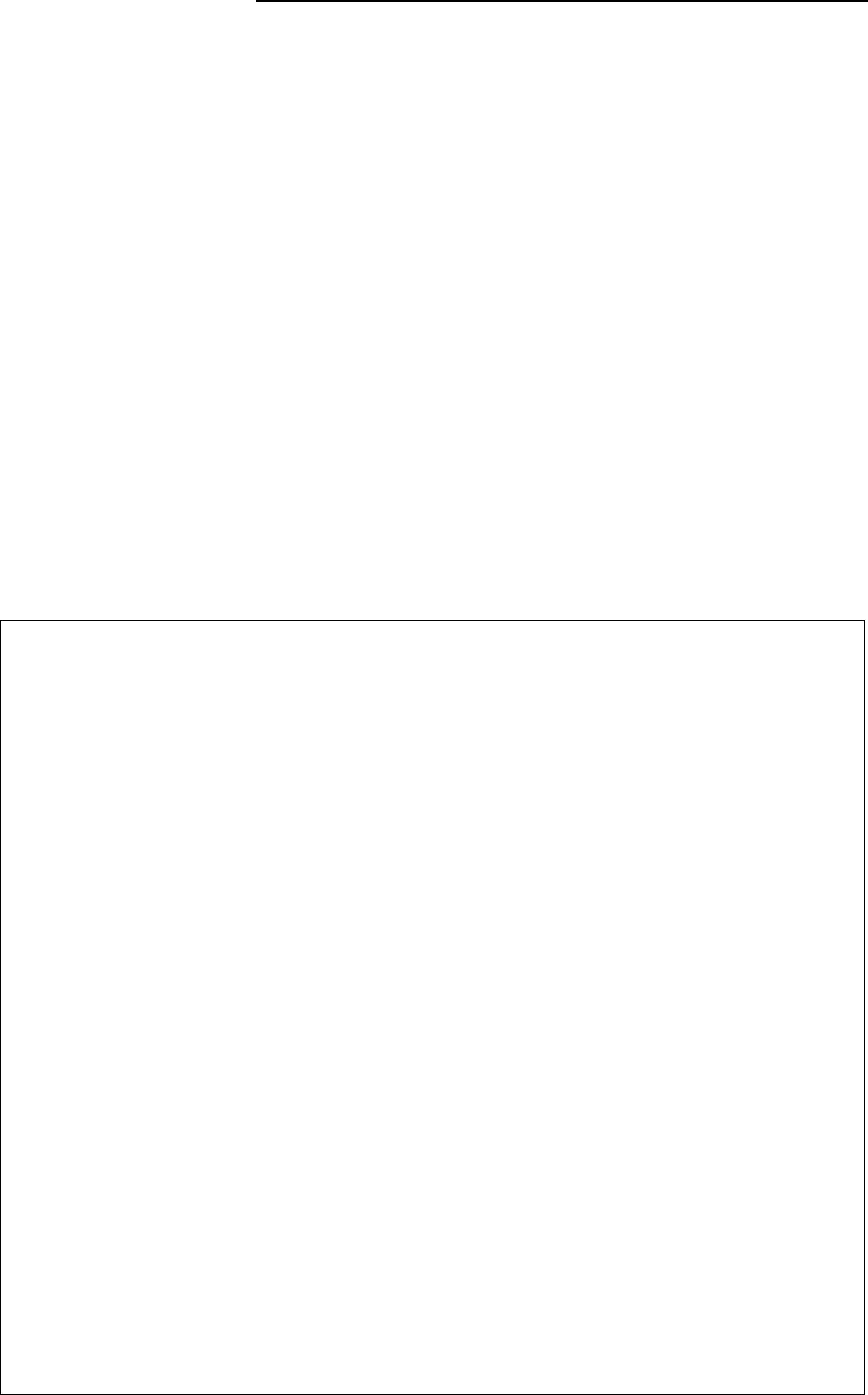

Historically, the Army has had more accidental losses, including

fratricide (friendly fire), than losses from enemy action. See Figure 1-1.

These accidental losses are the same types experienced in peacetime

Figure 1-1. Battle and Nonbattle Casualties

FM 100-14

1-3

during training exercises. These losses are not caused by the enemy or

an adversary. Factors include—

• An ever-changing operational environment.

• Effects of a fast-paced, high-operational tempo (OPTEMPO) and

a high-personnel tempo (PERSTEMPO) on unit and human

performance. Examples include leader or soldier err or or failur e

to train or perform to standards.

• Equipment failure, support failure, and the effects of the

physical environment.

PRINCIPLES

The basic principles that provide a framework for implementing

the risk management process are—

•

Integrating risk management into mission planning, preparation, and

execution.

Leaders and staffs continuously identify hazards and

assess both accident and tactical risks. They then develop and

coordinate control measures. They determine the level of residual

risk for accident hazards in order to evaluate courses of action

(COAs). They integrate control measures into staff estimates,

operation plans (OPLANs), operation orders (OPORDs), and

missions. Commanders assess the ar eas in which they might take

tactical risks. They approve control measures that will reduce

risks. Leaders ensure that all soldiers understand and properly

execute risk controls. They continuously assess variable hazards

and implement risk contr ols.

•

Making risk decisions at the appropriate level in the chain of command.

The commander should address risk guidance in his

commander’s guidance. He bases his risk guidance on

established Army and other appropriate policies and on his

higher commander’s direction. He then gives guidance on how

much risk he is willing to accept and delegate. Subordinates seek

the higher commander ’s approval to accept risks that might

imperil the next higher commander’s intent.

•

Accepting no unnecessary risk.

Commanders compare and balance

risks against mission expectations and accept risks only if the

benefits outweigh the potential costs or losses. Commanders

alone decide whether to accept the level of residual risk to

accomplish the mission.

Risk Management

1-4

APPLICABILITY

Risk management applies to all situations and environments

across the wide range of Army operations, activities, and

pr ocesses. Risk management is useful in developing, fielding, and

employing the total Army force. Figure 1-2 summarizes the key

aspects of risk management.

DEVELOPMENT

Development concerns include force design, manpower

allocation, training and training developments, and combat and

materiel developments (equipment and weapons systems) and

battle laboratories.

Risk management assists the commander or leader in—

• Conserving lives and resources and avoiding

unnecessary risk.

• Making an informed decision to implement a COA.

• Identifying feasible and effective control measures where

specific standards do not exist.

• Providing reasonable alternatives for mission

accomplishment.

Risk management does not—

• Inhibit the commander’s and leader's flexibility and

initiative.

• Remove risk altogether, or support a zero defects

mindset.

• Require a GO/NO-GO decision.

• Sanction or justify violating the law.

• Remove the necessity for standard drills, tactics,

techniques, and procedures.

Figure 1-2. Key Aspects of Risk Management

FM 100-14

1-5

Force Design

Concerns include risks introduced in trade-off decisions that

involve the design and equipping of—

• Tables of organization and equipment (TOE).

• Modification tables of organization and equipment (MTOE).

• Tables of distribution and allowances (TDA) organizations.

Manpower Allocations

Concerns include shortfalls in manning that put unit readiness

and full use of combat system capabilities at risk.

Training and Training Developments

Concerns include hazardous and critical training tasks and

feasible risk reduction measures that provide leaders with the

flexibility to safely conduct tough, realistic training.

Combat and Materiel Developments and Battle Laboratories

Concerns include providing a means to assist in making informed

trade-off decisions such as—

• Balancing equipment form, fit, and function.

• Balancing the durability and cost of equipment and spare parts

against their reliability, availability, and maintainability

requirements.

• Determining the environmental impact.

• Determining whether to accept systems with less than the full

capabilities prescribed in requirement documents and

experimental procedures.

ARs 70-1 and 385-16 and MIL-STD-882 provide details on risk

management application in the Army materiel acquisition process.

FIELDING

Fielding concerns include personnel assignments, sustainment

and logistics, training, and base operations.

Personnel Assignments

Concerns include making informed decisions in assigning

replacement personnel. For example, a risk is associated with

assigning a multiple launch rocket system crewmember as a

replacement for a tube artillery cannon crewmember.

Risk Management

1-6

Sustainment and Logistics

Concerns include enhancing one’s ability to determine support

requirements, the order in which they should be received, and the

potential impact of logistics decisions on operations.

Training

Concerns include helping leaders determine the—

• Balance between training realism and unnecessary risks

in training.

• Impact of training operations on the environment.

• Level of proficiency and experience of soldiers and leaders.

Base Operations

Concerns include prioritizing the execution of base operations

functions to get the most benefit from available resources. Examples

include allocating resources for pollution prevention, correcting safety

and health hazards, and correcting violations of environmental

protection regulations. FM 20-400 provides specific guidance on

environmental protection in military operations.

EMPLOYMENT

Employment concerns include force protection and deployment,

operations, and redeployment.

Force Protection

Concerns include developing a plan that identifies threats and their

associated hazar ds and balancing resource restraints against the risk.

Deployment, Operations, and Redeployment

Concerns include—

• Analyzing the factors of mission, enemy, terrain, troops, and

time available (METT-T) to determine both tactical and accident

risks and appropriate risk reduction measures.

• Determining the correct units, equipment composition, and

sequence.

• Identifying controls essential to safety and environmental

protection.

FM 100-14

1-7

CONSTRAINTS

Risk management does not convey authority to violate the law-of-

land warfare or deliberately disobey local, state, national, or host

nation laws. It does not justify ignoring regulatory restrictions and

applicable standards. Neither does it justify bypassing risk controls

required by law, such as life safety and fire protection codes, physical

security, transport and disposal of hazardous material and waste, or

storage of classified material. Commanders may not use risk

management to alter or bypass legislative intent. However, when

restrictions imposed by other agencies adversely affect the mission,

planners may negotiate a satisfactory COA if the result conforms to

the legislative intent.

Risk management assists the commander in complying with

regulatory and legal requirements by—

• Identifying applicable legal standards that affect the mission.

• Identifying alternate COAs or alternate standards that meet the

intent of the law.

• Ensuring better use of limited resources through establishing

priorities to corr ect known hazar dous conditions that will r esult

in projects with the highest return on investment funded first.