Fillable Printable Letter For Proposal For Business

Fillable Printable Letter For Proposal For Business

Letter For Proposal For Business

Formal Reports

and Proposals

9

T

he distinctions betw een formal and informal reports ar e often b lurred.Nev ertheless,

a formal report is usually written to someone in another company or organization.

Occasionally it is written for a senior manager in the same company,or for someone with

whom the writer has little regular contact. Usually it is longer than an informal report

and requires more extensive research.Unless you are a consultant,you are unlikely to be

asked to write a formal report often.When you are, there may be a lot riding on it—

including your reputation.

The purpose of this c hapter is to show you how to write a for mal repor t and how to

put together the kind of proposal that often pr ecedes it.As Figure 9-1 shows,man y of the

elements of for mal repor ts are the same as those for informal ones. You need to pay the

same attention to headings, lists, and illustrations, for example. Although much of the

advice in the previous chapter could be duplicated in this one,the emphasis here will be

on those areas where there’s a difference.

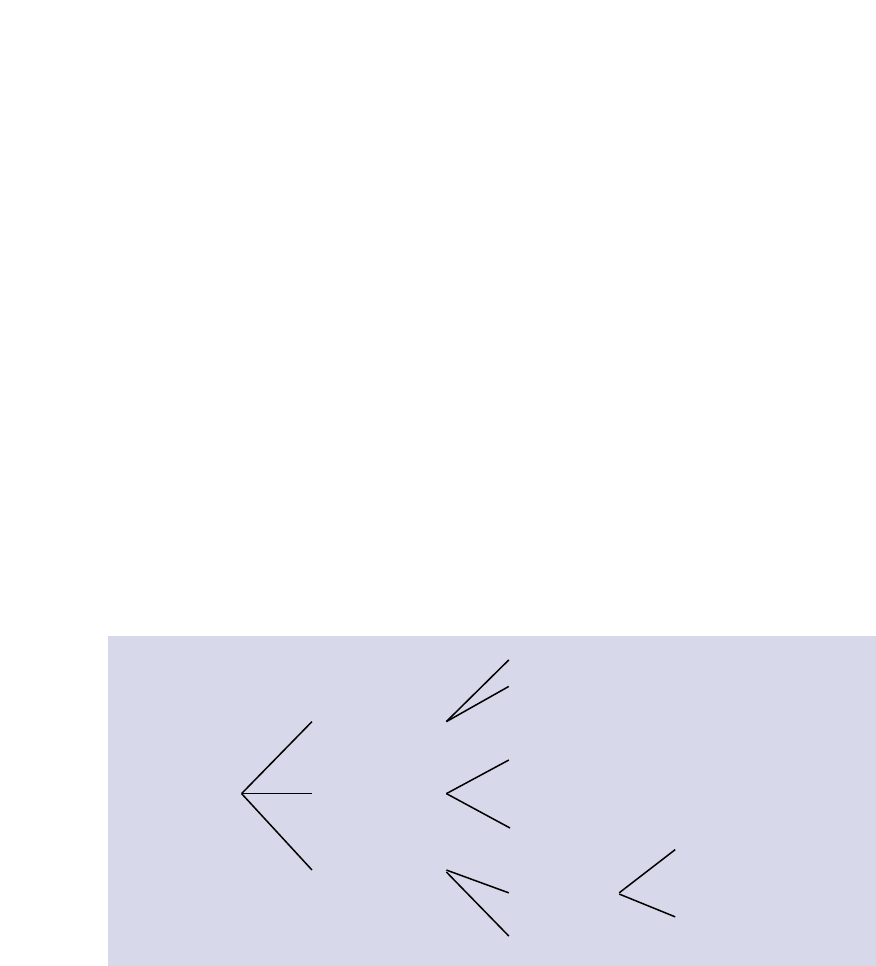

Figure 9-1 Contrasting Features of Informal and Formal Reports

Informal Formal

Reader often internal often external or distant

within organization

Length • usually short • usually long (3 pages or more)

• several sections • sections and subsections

Tone • personal • more impersonal

• contractions • no contractions

Summary integrated on separate page

Introduction no heading can have one or more headings

Title appears as subject line appears on separate title page

in memo heading

Transmittal page optional covering letter or memo

Contents page none useful if report is over 5 pages

The Four R’s of Planning

As emphasized earlier, the first step in planning any piece of correspondence is to think

about the reason for writing and about the receiver. For a long, for mal report you need

to add two more R’s to your planning sheet:restrictions and research.

Assessing the Reason for Writing and the Receiver

As discussed in Chapter 2, formal reports are usually less personal than informal ones.

They omit the contractions of personal conversation and tend to name fewer individuals.

Traditionally, formal reports have tried to give a sense of objectivity by omitting the

personal I.As a result, passages were often convoluted and difficult to read.While I-free

reports are still the practice in some circles, business writers are increasingly using I in

formal reports to produce clearer and more forceful writing. (In informal reports,

personal pronouns are not only tolerated but recommended.) However,avoid “I think”or

“in my opinion” phrases when you can complete the thought without them:

X I found that the fittings were defective.

√ The fittings were defective.

X In my view, the market value will rise in the spring.

√ Market value will probably rise in the spring.

If you are par t of a group,you can also refer to we, since the collective weight of a g roup

seems more objective than that of an individual.In any case,use I rather than referr ing to

yourself imper sonally as the writer or the author.

Determining Restrictions

What are the limitations on the resources that will be available to help you with the

report?

1. Financial What will be your budget? What expenses will be involved and

is the budget adequate to cover them?

2. Personnel Will you have the services of a good typist or illustrator? Will

outside help be required?

3. Time What is your deadline? Create a realistic time line on a graph with

the various stages of the repor t plotted on it at specific dates—so many days

or weeks for researc h, organizing,writing,editing, and final production.The

larger the task,the more impor tant these self-imposed dates become.In

193Chapter 9 Formal Reports and Proposals

allocating time,you may be wise to leave a margin of er ror for delays,

whether from bureaucratic mix-ups or postal problems.

Deciding on Research

Before beginning your research, explore the subject itself to avoid taking too narrow a

path and overlooking important alternatives.Good questions are an effective stimulus for

seeing different perspectives on an issue.Here are some ways to start:

1. Brainstorming By yourself or with a colleague,blitz the subject.Jot

down all the questions you can think of that relate to the topic,in whatever

order they occur. Don’t be negative or rule anything out at this point.

2. Tree Diagram Assume that the subject is the tr unk and add as many large

and small branches as you can to represent the different aspects of the

subject.Again,think of the branches as questions.Tree diagramming can be

useful by itself or as a second stage of random brainstorming.

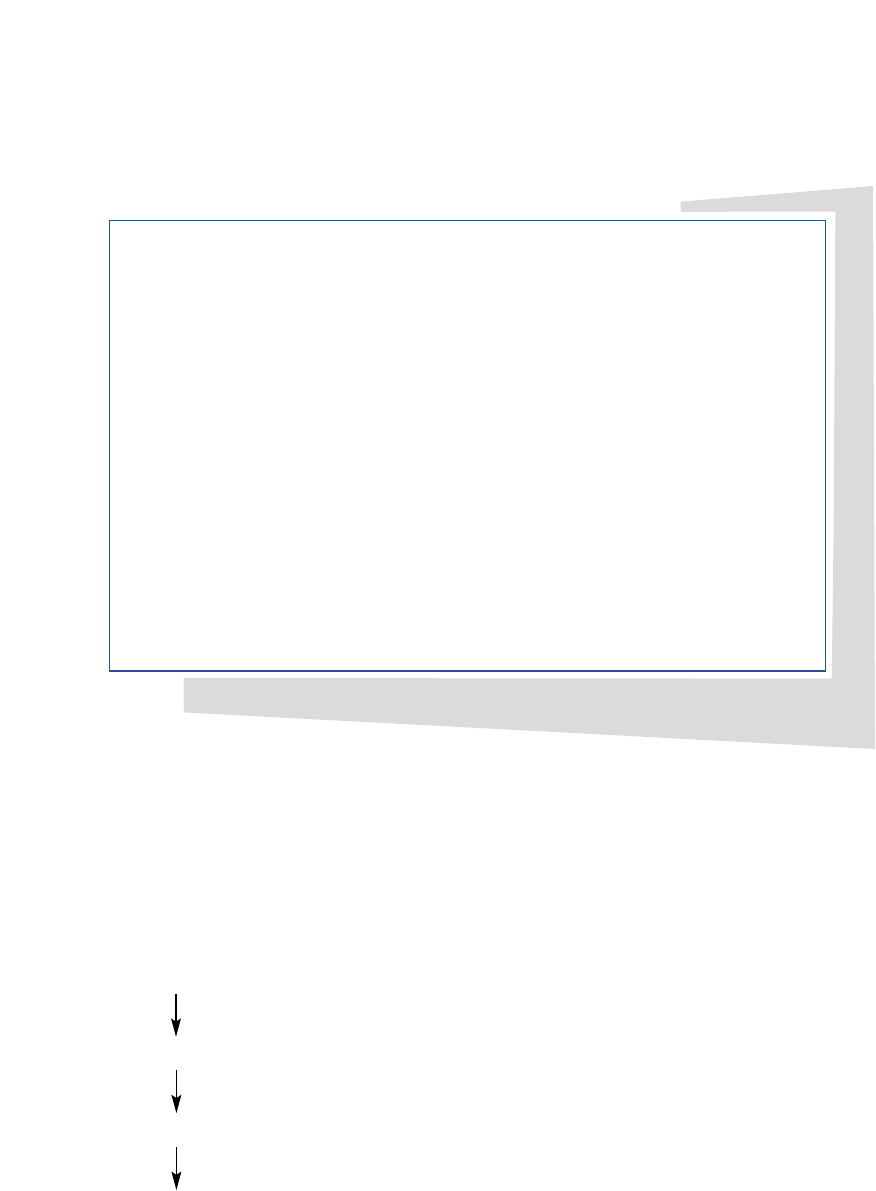

Figure 9-2 Example of a Tree Diagram

budget cut

stale approach

Advertising

Weakness

outdated design

Reasons for

Product Lag

Drop in Sales

new features needed

consumer spending down

Price Resistance

poor economy

product a luxury item

cheap imports

3. Journalist’s Approach In researching a stor y,jour nalists consider the

W’s of repor ting:Who? What? When? Where? Why? For your research

planning,try asking the same five questions and add another:How? Use the

basic questions to for mulate other subquestions.

4. The 3C Approach A more thorough way to explore a topic is to ask

questions about three areas:

194

Impact: A Guide to Business Communication

• Components How can the subject be divided? How many different ways

are there to partition it?

• Change What are the changed or c hang ing elements of the subject? What

are the causes or effects of cer tain actions? What trends are there?

• Context What is the larger issue or field into whic h this subject fits? How

have other s dealt with the problems associated with the subject?

Once you have stretched your mind exploring the possibilities of a subject, move in the

other direction.Think of limiting the subject and working out the precise focus of your

study.Weigh the time and expense of the research against its impor tance to the report.

Remember that it’s better to do a limited topic well than a broad one superficially.

Finding Information

1. Use librarians. For some of your researc h you may have to turn to

government documents or academic studies.Librarians can be a g reat help

in finding infor mation or showing the fastest way to get it.

2. Do a computer search. Most librar ies now have access to extensive

databases that allow you to source needed infor mation quickly by computer.

For example, a computer searc h can show you where to find all the ar ticles,

books,and reviews on a topic. It can itemize a cer tain kind of transaction or

economic activity over a given period of time.CD-ROM indexes enable you

to search by author,by title,or by keyword, sometimes g iving br ief

summaries or even the full text of each ar ticle.When you enter the

keywords that descr ibe the limits of your topic (for example,free trade,

auto par ts, Canada), the computer searc h will list the material relating to

that combination of terms.Although much of the same reference mater ial is

available in books,your library may not have all of them, or they may not be

as up to date as the computerized material. Besides, it’s a muc h slower

process to search through books.

A librarian can guide you to the most relevant database for your topic.

3. Access infor mation online. E-mail and the Inter net provide access to

newsgroups,discussion lists,and forums that focus on specific subjects.

Possibly the most powerful research tool of all, however, is the World Wide

Web.Using searc h engines suc h as AltaVista or Excite or a directory suc h as

Yahoo,you can look for online articles on any subject.Today writing and

research is commonly published on a Web site,providing a r ic h source of

infor mation,par ticularly on current subjects.

195Chapter 9 Formal Reports and Proposals

4.Look for inside sources. If you are doing a repor t on a par ticular

company or organization,don’t overlook the most accessible source of

infor mation—inter nal records and the employees themselves.Many an

unsuspecting repor t wr iter has spent days searc hing for facts readily

available in inter nal files.If the topic is one of continuing concern to the

company,chances are that someone has looked at it,or an aspect of it,

before.Some of the facts from an earlier investigation may be out of date,

but it’s likely that other infor mation is timely and relevant.

Even when an earlier repor t doesn’t exist, it is still sensible to find out if

other people have worked on the topic.They are usually glad to discuss the

issues.A short telephone inquir y or memo may save you valuable research

time or give you helpful suggestions for your exploration.Reinventing the

wheel does nobody any good.

5. Check the reliability of information. Establish whether any of the

second-hand facts you get from your research will need verifying.

Remember that a source with a special interest may exaggerate or gloss over

cer tain infor mation, often unconsciously. Even statistical data should

undergo scr utiny.Any obser ver of election polls and campaigns knows that

while statistics may not lie,they can cer tainly distor t. If you have to get

fresh data through a questionnaire or sur vey,make sure the results are as

reliable and valid as possible.If you are not familiar with proper sampling

techniques and have no knowledge of statistical reliability,consult someone

who is competent in those areas.The cost of obtaining outside help may be

less than the cost of losing your credibility through faulty data.

Managing Information

1. Use file cards. In doing lengthy research,many people find that file cards

are an efficient way to record and keep trac k of details.Use a separate card

for each different item of infor mation you gather—whether the item is an

opinion or an impor tant statistic. You can then shuffle the cards according to

the order you have chosen for the findings.Drafting the findings section of a

repor t is much easier if the sequence of information is already in front of

you.

196

Impact: A Guide to Business Communication

If you are gathering information from a published source,remember to

include the bibliographical infor mation on the card (author,title,publisher,

place of publication, and page number) so that you don’t have to spend time

chasing down the reference later.

2. Create an outline. Some writer s find that they work best by banging out

a first draft as quic kly as possible without wor rying about details.Others

work best when they have a detailed plan in front of them.It doesn’t matter

what method you c hoose,as long as at some point you carefully ar range the

material so that each little bit is in the best place.Although with a shor t

infor mal repor t you may not feel the need for an outline,with lengthy

for mal repor ts an outline is almost a prerequisite for avoiding muddles.

The outline can be in point for m or in full sentences.Numbering eac h

section will help you keep in mind the relative value of each.Whichever

numbering system you use for your outline,you can repeat it in the body of

the repor t and in the table of contents.

Figure 9-3 Example of a Point-Form Outline

Reasons for Drop in Sales

1. Advertising Weakness A. Budget cut

B. Stale approach

2. Product Lag A. Outdated design

B. Need for new features

3. Price Resistance A. Poor economy

i. consumer spending down

ii. product a luxury item

B. Cheap imports

Organizing Formal Reports

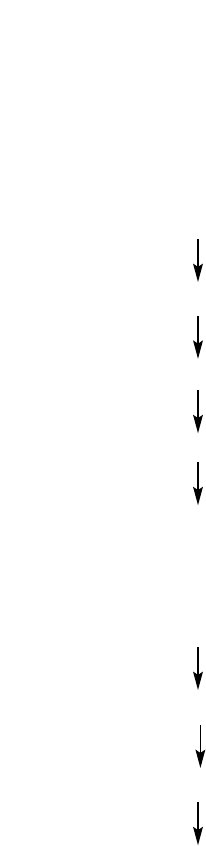

Although many var iations are possible, a typical repor t structure looks like Figure 9-4.

Since you will begin your writing process with the main section,let’s begin by looking

at var ious methods of str uctur ing the body of your repor t.

197Chapter 9 Formal Reports and Proposals

Main Section

Although the sections will vary according to the subject,the basic principles of organizing

are the same as for informal reports.

For readers who will be interested or pleased, use the direct approach. Here is the

most common model:

Summary

Introduction

Recommendations and/or Conclusions

Discussion of Findings

198

Impact: A Guide to Business Communication

Figure 9-4 Structure of a Formal Report

Front Section Title Page

Letter of Transmittal

Table of Contents

Main Section Summary

Introduction

Discussion of Findings

Conclusions and Recommendations

Back Section References

Appendix

A less common variation of this direct approach is useful when there is a lengthy list of

recommendations:

Summary

Introduction

Summary of Recommendations

Discussion of Findings

Details of Recommendations

When readers will be displeased or skeptical, the indirect approach will lead them

gradually toward the conclusions or recommendations:

Summary

Introduction

Discussion of Findings

Conclusions and/or Recommendations

The indirect approach is sometimes used in government and consulting circles, even

when the readers are interested. The trend is toward the direct approach, however,

especially for busy readers.

The preceding suggestions are not an ironclad prescription for every repor t.You may

want to change or add some sections. You may also have to adapt the following advice

about what to put in each section. Let ease of under standing be the guide.

Summary

A summary for a formal report—often called an executive summary—is really a

condensation of the most important points.Unlik e the introductory summary that begins

most shor t informal repor ts, the summar y for a formal repor t is put on a separate page

with a heading. It’s not an introduction to the report, but a synopsis—the report

199Chapter 9 Formal Reports and Proposals

condensed. It’s a convenience for the reader and may be the only part that senior

management reads,but the repor t can make sense without it.For this reason,it’s best to

write the summar y after you have completed the body of the repor t.

The summary doesn’t have to g ive equal weight to all sections of the repor t. It often

has only a brief account of the backg round or methodology, and may even omit them if

they are unimportant. By contrast, it usually pays most attention to the conclusions or

recommendations. On rare occasions, if the list of recommendations is lengthy, the title

may be simply “Summar y of Recommendations.”

Generally in a summary it’s best to follow the order of the report.That is,if the report

takes the direct approach, so should the summary. Similarly, if the repor t has an indirect

order,the summary should be indirect.

In the interest of brevity:

• use lists where possible;

• omit examples,unless the example is a key finding;

• stick to the facts, avoiding unneeded references to the repor t itself. For

example,instead of saying,“The Findings section reveals . ..” simply put a

heading,“Findings,”and list the facts.

Since there is a subtle psycholog ical bar r ier to tur ning a page,especially for a reader who

is extremely busy, try to keep the summary to a single sheet. If this seems an impossible

task for a complicated or length y r eport,remember Winston Churchill’s instruction to the

First Lord of the Admiralty in the midst of the Second World War:“Pray state this day,on

one side of a sheet of paper, how the Royal Navy is being adapted to meet the conditions

of moder n warfare”(Ogilvy,1983,p.35). Is your task more difficult than this one?

Introduction

This section may have a heading other than “Introduction,” depending on the focus, and

may have several subsections.It can include several or all of these topics:

• Purpose As in an infor mal repor t, a one-sentence explanation may be

enough.

• Background Many repor t wr iter s make the mistake of g iving too much

backg round. Include only the information needed to put the repor t in

perspective.If explaining the reasons for the repor t, a total history is rarely

needed.Focus on those conditions that have influenced the purpose and

design of the repor t.If you do have to include a lot of material,you should

probably have a separate section on background.

200

Impact: A Guide to Business Communication

• Scope Here you define the topic precisely and reveal any assumptions you

have made affecting the direction or boundaries of your investigation. If

there are constraints or difficulties that limit the study in some way, say

what they are.By doing so,you will help forestall criticisms that you didn’t

cover the area properly.

• Method If your findings are based on a questionnaire or sur vey of some

sor t, outline the steps you took.Repor ts with a heavy scientific emphasis

often include an explanation of the technical processes used in the

investigation.The process of infor mation-gathering is especially relevant

when the data is “soft”—that is,open to dispute.Again, if the explanation is

lengthy,consider putting it as a separate section.

Discussion of Findings

This is the largest section in most formal reports, and discusses the details of your

investigation,the facts on which you have based your conclusions or recommendations.It

should be subdivided,with numbered and descr iptive subheadings.(It may be possible to

give the section itself a more specific heading than “Discussion” or “Findings.”)

In choosing the best arrangement for findings,remember tha t the most effectiv e order

is the one that most easily leads the reader to the conclusions or recommendations.As

with informal reports, you can arrange findings by category or topic, by geographic or

chronolog ical order, or by order of impor tance.

How many subsections should a repor t have? It’s a matter of judgment.Don’t have so

many that the section is more like a long shopping list than a discussion. On the other

hand,don’t have so few that there’s a thic ket of information in eac h one.

Conclusions and/or Recommendations

While some repor ts have both conclusions and recommendations, many have one or the

other. Conclusions are the inferences you have made from your findings;

recommendations are suggestions about what actions to take. A long, research-based

report generall y gives conclusions;a pr oblem-solving r eport,r ecommendations .Her e are

some tips for both types:

• If there are several recommendations or conclusions,separate them in a list

or in subsections.

• Nor mally, put the most impor tant recommendation (or conclusion) first. If

you face a skeptical or hostile reader, however,you might make an

exception,and put the most controversial recommendation last,even if it is

the major one.

201Chapter 9 Formal Reports and Proposals

• Number the recommendations or conclusions,making them easier to refer

to. Number s will also reinforce the fact that there are more than one.

Otherwise,in later discussions the reader may focus on the most important

or controversial point and forget that there are others.

• Be as specific as possible about how eac h recommendation should be carr ied

out and who should be responsible.Some repor ts have an implementation

subsection for each recommendation.Others have a specific action plan at

the end of the repor t,outlining all the steps that should be taken.

• If implementation details are not feasible,consider including a

recommendation to set up an implementation committee or task force.If

your recommendations do include the details of implementation,suggest a

follow-up mechanism so that manager s or depar tments will get feedbac k on

the results.

With the main section of the repor t in place,you are now ready to add the pages for the

front and back sections.

Front Section

Title Page

Centre the information and arrange it so that it extends downward over most of the

length of the page.Include:

• the title of the repor t,in bold type or in capital letter s

• the name and title of the intended reader

• the name of the writer and the wr iter’s title (or the name of the firm, if the

repor t is by an outside consultant)

• the date

Letter of Transmittal

A letter of transmittal is a covering letter, given in letter or memo form, depending on

whether it is going to someone outside or inside the writer’s organization.It provides the

extra personal touc h that for mal repor ts generally lac k.A covering letter is usually brief

and follows this pattern:

• an opening statement,“transmitting”the repor t to the reader and stating its

title or purpose (for example,“Here is the repor t you requested on ...”)

• a brief outline of the major conclusions or recommendations

202

Impact: A Guide to Business Communication