Fillable Printable Cost-Benefit Analysis Sample

Fillable Printable Cost-Benefit Analysis Sample

Cost-Benefit Analysis Sample

www.vtpi.org

250-360-1560

Transportation Cost and Benefit Analysis

Techniques, Estimates and Implications

Second Edition (2009)

Executive Summary

Full report available at www.vtpi.org/tca

16 March 2011

By

Todd Alexander Litman

Victoria Transport Policy Institute

With Eric Doherty

Abstract

This 500+ page document is a comprehensive study of transportation benefit and

costing, and a guidebook for applying this information. It includes detailed analysis of

various transport costs and benefits. These impacts are described in detail and

categorized by various attributes: whether they are internal or external, fixed or variable,

market or nonmarket. Using the best available data, it provides monetized estimates of

twenty three costs for eleven travel modes under three travel conditions.

This document is unique in several important ways. It is one of the most comprehensive

studies of its kind, including many often-overlooked impacts. It is the only transport cost

study regularly updated as new information becomes available. It explains economic

concepts and evaluation techniques. It provides costs values in a format designed to

help users easily apply this information to policy analysis and planning situations. It

includes a spreadsheet that automates cost analysis. It discusses the implications and

applications of analysis results. It provides extensive references, many available through

the Internet, so users can obtain more detailed information as needed.

This study indicates that on average about a third of automobile costs are external and

about a quarter are internal but fixed. Fuel efficient and alternative fuel vehicles tend to

have somewhat lower external costs. Transit tends to have lower total costs under

urban-peak conditions. Ridesharing tends to have the lowest marginal costs.

Motorcycles tend to have relatively high costs due to their high crash risk. Nonmotorized

modes (walking and cycling) have minimal external costs. This study describes various

policy and planning reforms that can help increase economic efficiency and equity.

Transportation Cost and Benefit Analysis II – Executive Summary

Victoria Transport Policy Institute (www.vtpi.org)

16 March 2011 www.vtpi.org/tca/tca00.pdf

Page ES-2

Introduction

Smart consumers investigate all costs and benefits before making major purchase

decisions. Prior to buying a car you want accurate information on its fuel, maintenance,

repair and insurance costs. Similarly, before buying a train or airline ticket you want to

know about all fees and taxes, and the ease of schedule changes. You also want

information on each option’s reliability, comfort and safety. Just as consumers need

accurate and comprehensive information when making personal travel decisions,

communities need accurate and comprehensive information on all significant impacts

when making transport policy and planning decisions.

Transportation policy and planning decisions often involve tradeoffs between conflicting

objectives. For example, strategies to increase vehicle travel speeds can increase crash

risk and degrade walking conditions. This guidebook provides a framework for

evaluating and rationalizing such decisions. It examines how benefits and costs vary for

different travel modes and conditions. It supports more comprehensive planning analysis

by providing benefit and cost information in a convenient and flexible format.

Cost Analysis Framework

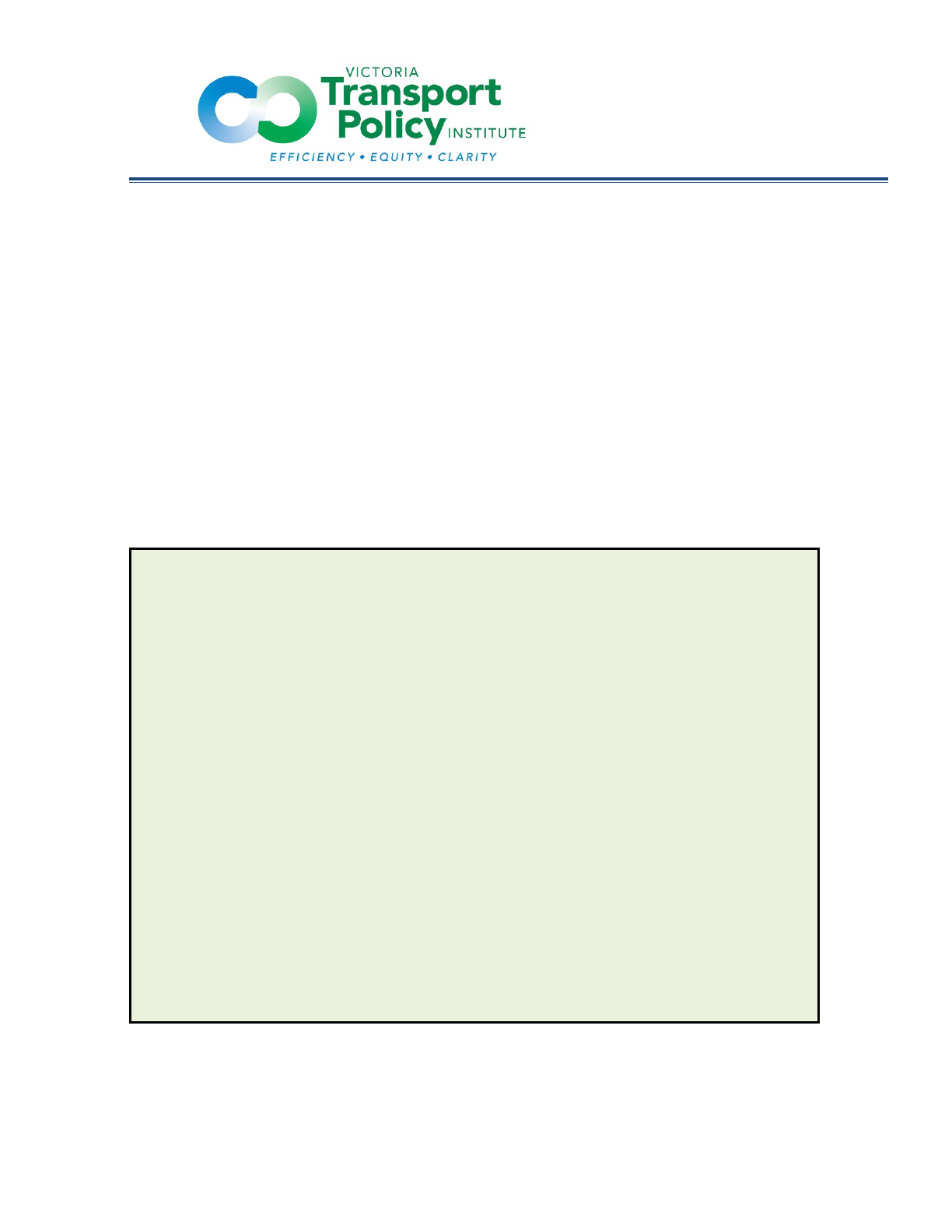

Table 1 lists the twenty-three transportation costs evaluated in this report.

Table 1

Transport Cost Categories

Cost Description

Vehicle Ownership Fixed costs of owning a vehicle.

Vehicle Operation Variable vehicle costs, including fuel, oil, tires, tolls and short-term parking fees.

Operating Subsidies Financial subsidies for public transit services.

Travel Time The value of time used for travel.

Internal Crash Crash costs borne directly by travelers.

External Crash Crash costs a traveler imposes on others.

Internal Activity Benefits Health benefits of active transportation to travelers (a cost where foregone).

External Activity Benefits Health benefits of active transportation to society (a cost where foregone).

Internal Parking Off-street residential parking and long-term leased parking paid by users.

External Parking Off-street parking costs not borne directly by users.

Congestion Congestion costs imposed on other road users.

Road Facilities Roadway facility construction and operating expenses not paid by user fees.

Land Value The value of land used in public road rights-of-way.

Traffic Services Costs of providing traffic services such as traffic policing, and emergency services.

Transport Diversity The value to society of a diverse transport system, particularly for non-drivers.

Air Pollution Costs of vehicle air pollution emissions.

Greenhouse Gas Pollution Lifecycle costs of greenhouse gases that contribute to climate change.

Noise Costs of vehicle noise pollution emissions.

Resource Externalities External costs of resource consumption, particularly petroleum.

Barrier Effect Delays that roads and traffic cause to nonmotorized travel.

Land Use Impacts Increased costs of sprawled, automobile-oriented land use.

Water Pollution Water pollution and hydrologic impacts caused by transport facilities and vehicles.

Waste External costs associated with disposal of vehicle wastes.

This table defines the 23 transport cost categories evaluated in this study.

Transportation Cost and Benefit Analysis II – Executive Summary

Victoria Transport Policy Institute (www.vtpi.org)

16 March 2011 www.vtpi.org/tca/tca00.pdf

Page ES-3

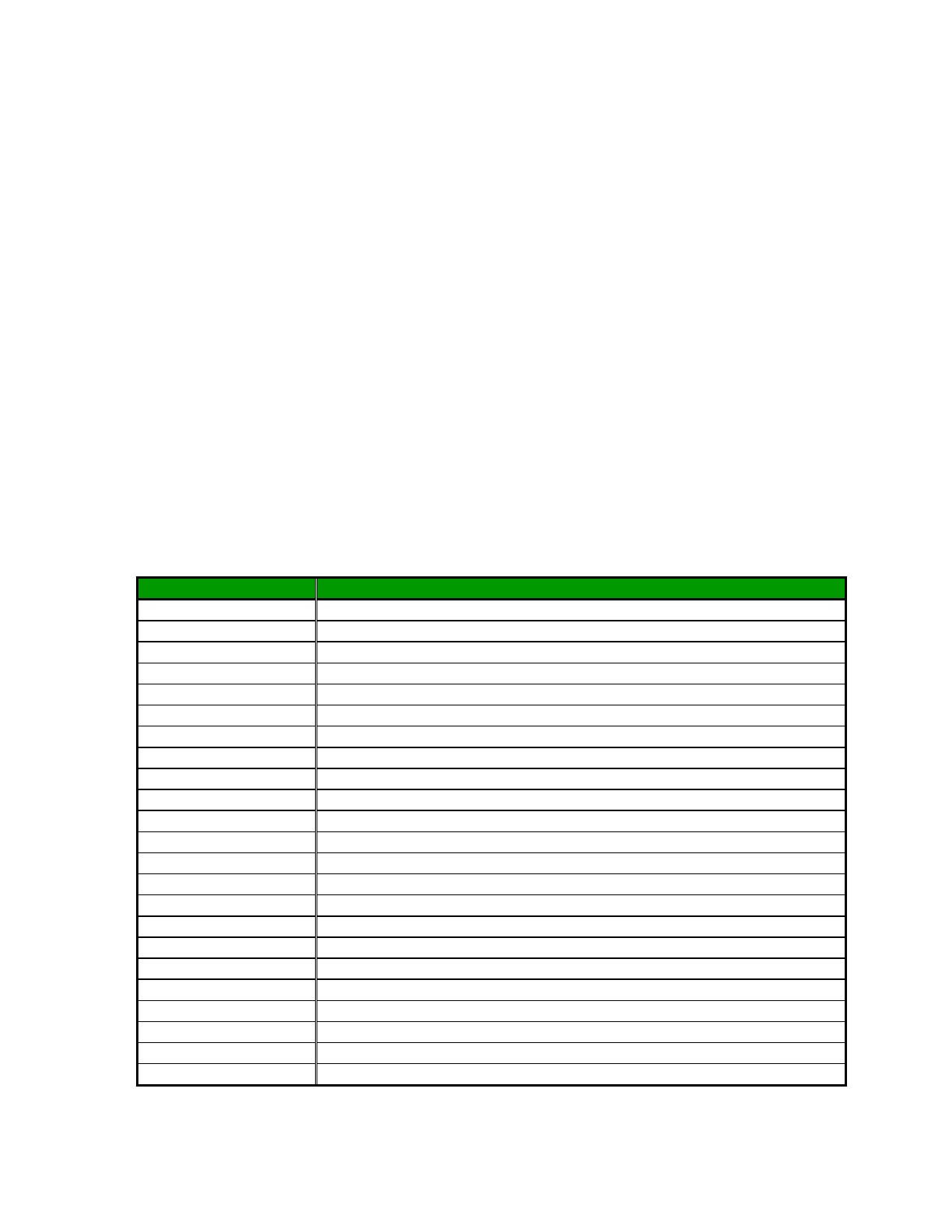

Table 2 categorizes these costs according to whether they are internal (users bear them

directly) or external (imposed on non-users), variable (related to the amount of travel) or

fixed, and market (involve goods regularly traded in competitive markets) or non-market.

Table 2

Transportation Cost Categories

Cost Internal/

External

Variable/

Fixed

Market/

Non-Market

Cost Internal/

External

Variable/

Fixed

Market/

Non-Market

1. Vehicle ownership Internal Fixed Market 13. Roadway land value External Fixed Market

2. Vehicle operation Internal Variable Market 14. Municipal services External Variable Market

3. Operating subsidies External Fixed Market 15. Equity & option value External Variable N-M

4. Travel time Internal Variable N-M 16. Air pollution External Variable N-M

5. Internal crash Internal Variable N-M 17. Greenhouse gas External Variable Mixed

6. External crash External Variable Mixed 18. Noise External Variable N-M

7. Internal activity* Internal Variable Mixed 19. Resource consumption External Variable Mixed

8. External activity* External Variable Mixed 20. Barrier effect External Variable N-M

9. Internal parking Internal Fixed Market 21. Land use impacts External Fixed Mixed

10. External parking External Variable Market 22. Water pollution External Variable N-M

11. Congestion External Variable Mixed 23. Waste disposal External Variable N-M

12. Road facilities External Variable Market

This table lists the 23 costs identified in the study and indicates how they are distributed.

Table 3 describes the eleven transport modes evaluated in this study. Monetized

(measured in monetary values) estimates are developed of each cost for each mode under

three travel conditions (urban-peak, urban off-peak and rural) in 2007 U.S. dollars per

vehicle-mile. These cost estimates are based on extensive research, including the results

of previous studies updated to reflect inflation and other changes, and some original

analysis. This guidebook includes a chapter concerning each cost category, with detailed

analysis and extensive references.

Table 3

Transport Modes

Mode Description

Average Automobile A medium sized car that averages 21 mpg overall (16 mpg city driving, 24 mph

highway driving), averaging 1.5 overall and 1.1 Urban-Peak occupancy.

Compact (Fuel

Efficient) Car

A small four passenger car that averages 40 mpg overall (34 mpg city driving, 46 mpg

highway driving).

Electric Car A medium size electric car that averages 0.5 kWh per mile fuel efficiency.

Van or Light Truck

A 14 passenger van or light truck that averages 15 mpg overall (14 mpg city and 20

mph highway driving). Occupancy is same as an automobile.

Rideshare Passenger. The incremental cost of an additional passenger.

Diesel Bus A 40 foot bus with 25 peak and 8 Off-Peak passengers, averaging 4.0 mpg.

Electric Bus/Trolley

A 65 passenger bus or trolley with 30 peak and 10 off-peak passengers, averaging 6.5

mpg energy consumption equivalent.

Motorcycle A medium size motorcycle 45 mpg urban and 55 mph rural average fuel efficiency.

Bicycle A moderate priced bicycle ridden an average of 10 mph.

Walk A person walking an average of 3 mph.

Telework Two 11 mile commute trips avoided when employees work from home.

This table describes the eleven transport modes evaluated in this study.

Transportation Cost and Benefit Analysis II – Executive Summary

Victoria Transport Policy Institute (www.vtpi.org)

16 March 2011 www.vtpi.org/tca/tca00.pdf

Page ES-4

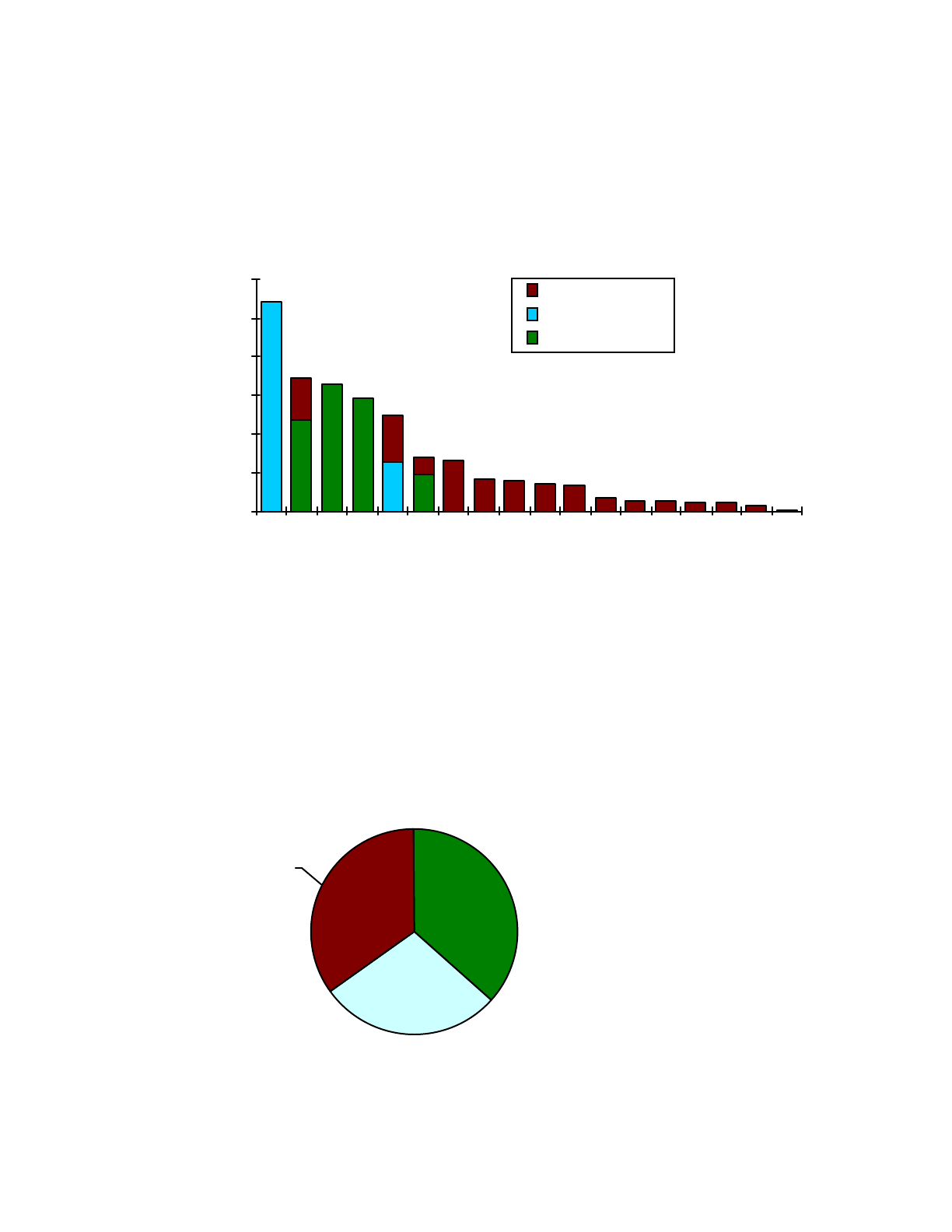

Figure 1 illustrates the costs for an Average Car ranked by magnitude, with internal and

external components combined. This shows that the largest categories of costs tend to be

internal, including vehicle ownership, travel time, vehicle operation and crash risk borne

directly by individual motorists. External costs tend to be smaller, and so are easy to

overlook, but numerous, so their aggregate value tends to be significant.

Figure 1 Average Automobile Costs

$0.00

$0.05

$0.10

$0.15

$0.20

$0.25

$0.30

Vehicle Ownership

Crash

V

eh

i

cle

Oper

at

ion

T

ravel Time

Parki

ng

Roa

d

Facilities

Land Use Impacts

Congest

i

on

Res

our

ces

Air Pollut ion

Land

Va

lue

G

reenhouse Gas

W

at er

Bar

r

i

er E

ffe

ct

Traffic Serv

i

ces

Noise

Tran

s

por

t

Diversi

t

y

Was

t

e

Dollars Per Vehicle Mile

External Costs

Internal Fixed

Internal Variable

This figure shows Average Car costs per vehicle mile, ranked by magnitude. External costs tend

to be small but are numerous.

Figure 2 shows the distribution of costs aggregated. About a third of total costs are

External and about a quarter are Internal-Fixed, leaving less than half Internal-Variable,

indicating significant underpricing (prices are significantly below total costs).

Figure 2 Average Car Cost Distribution

Internal

Variable

37%

External

35%

Internal Fixed

28%

This figure illustrates the aggregate distribution of costs for an average car. About 60% of total

vehicle costs are either External or Internal-Fixed.

Transportation Cost and Benefit Analysis II – Executive Summary

Victoria Transport Policy Institute

(www.vtpi.org)

16 March 2011 www.vtpi.org/tca/tca00.pdf

Page ES-5

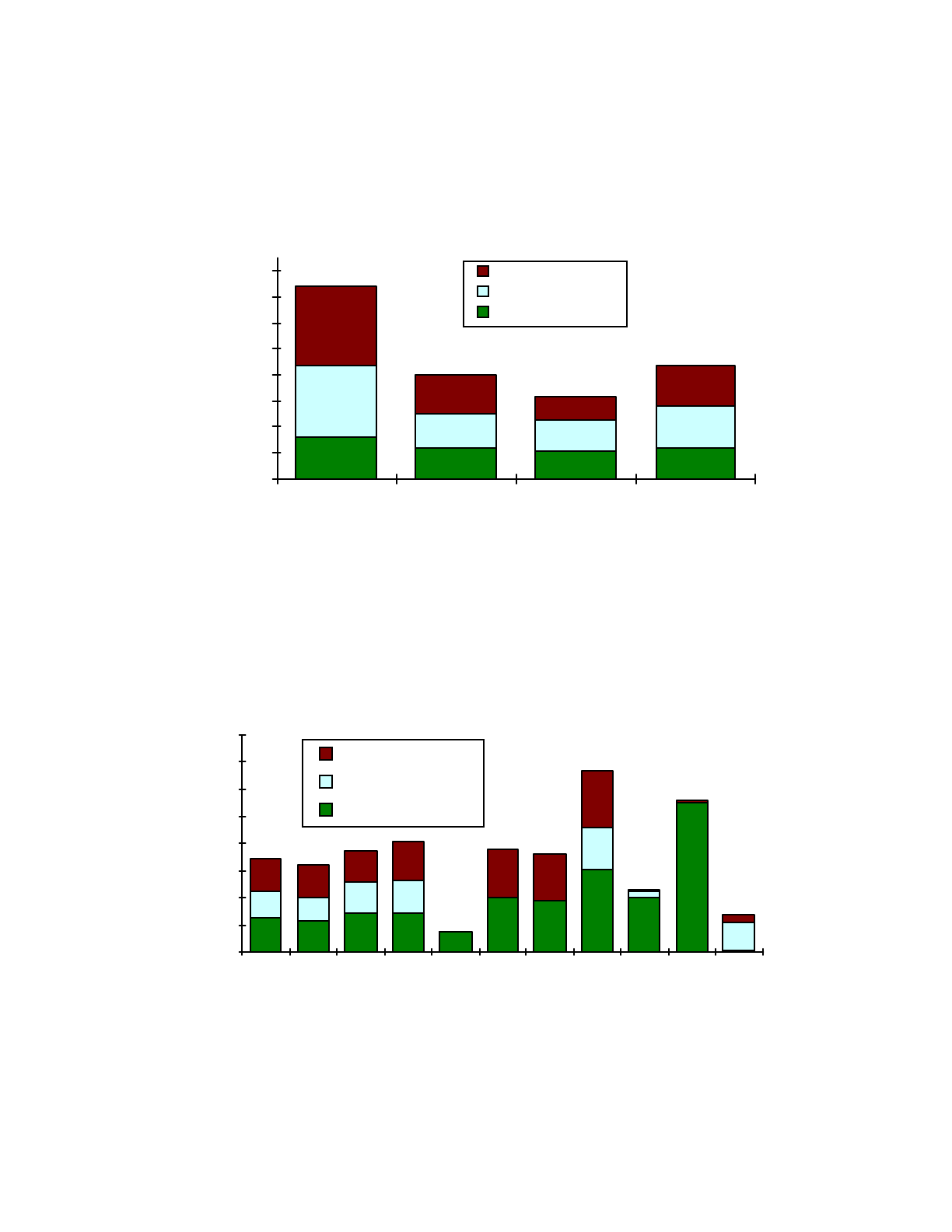

Figure 3 shows the distribution of costs per passenger-mile, calculated by dividing costs

per vehicle-mile by average vehicle occupancy. Urban-peak travel has relatively high

costs because peak-period vehicle occupancy tends to be lower than average (1.1

passengers per vehicle compared with 1.42 for other travel conditions).

Figure 3

Average Car Costs Per Passenger-Mile

$0.00

$0.20

$0.40

$0.60

$0.80

$1.00

$1.20

$1.40

$1.60

Urban Peak Urban Off-Peak Rural Average

Dollars Per Passenger-Mile

External

Internal Variable

Internal Fixed

This figure illustrates how aggregate costs per passenger-mile vary by travel conditions, taking

into account differences in vehicle occupancy. Urban-peak vehicle occupancy is low; therefore

urban peak passenger mile costs are high compared to the other categories.

Figure 4 compares costs per passenger-mile for each of the eleven modes. Both the

magnitude and the distribution of costs vary significantly between modes.

Figure 4

Cost Distribution by Mode

$0.00

$0.25

$0.50

$0.75

$1.00

$1.25

$1.50

$1.75

$2.00

Average Automobi

l

e

C

o

mpact Car

Electric Car

Van/ Light Truck

Rideshare

Pa

ssenger

Diesel Bus

Ele

ctric Bu

s

/ Trolley

M

otorcyc le

Bike

Walk

Tel

ework

Dollars Per Passenger-Mile

External

Internal Fixed

Internal Variable

This graph shows the cost distribution of each mode. Transit costs are based on average U.S.

ridership levels and would be lower in areas with higher ridership rates.

Transportation Cost and Benefit Analysis II – Executive Summary

Victoria Transport Policy Institute

(www.vtpi.org)

16 March 2011 www.vtpi.org/tca/tca00.pdf

Page ES-6

Implications

This analysis indicates that a major portion of transportation costs are external, fixed and

non-market. On average, each dollar spent on vehicle operating expenses imposes about

$2.55 in total costs to society. External and fixed costs represent underpricing. This cost

profile is inequitable and leads to economically excessive motor vehicle travel that

exacerbates various economic, environmental and social problems.

Non-market costs tend to be undervalued in transportation planning. These costs are

significant in magnitude compared with impacts normally considered. Failure to consider

these costs can lead to decisions that result in negative net benefits. For example, society

is overall worse off if a roadway expansion saves motorists 5¢ per mile in average travel

time costs but imposes 10¢ per mile on average in additional economic and

environmental costs.

Applications

Comprehensive economic analysis can be used in many planning applications:

• Transportation policy analysis. Establish strategic goals and objectives taking into

account all impacts, including those that are indirect and long-term.

• Transportation pricing. Develop more efficient prices that reflect the full costs.

• Investment policies. Account for all impacts when determining which transport

investments are overall optimal.

•

Transportation equity analysis. Consider all impacts, including those that are indirect and

non-market, when evaluating equity.

•

Transportation Demand Management analysis. Consider all impacts when evaluating

strategies that reduce total vehicle travel and encourage use of alternative modes.

Conclusions

If you ask people what it costs to drive they typically mention vehicle operating

expenses, which average approximately 16¢ per mile for a typical car. Some may also

include a portion of vehicle ownership costs, which average about 27¢ per mile. A few

may also mention the value of their travel time and accident risk. These, however, are

only a portion of total costs. The full cost of driving includes these internal costs plus

several external costs. Total costs range from about $0.94 per vehicle mile for rural

driving to $1.64 for urban peak driving. Of course there is considerable variation in the

cost of any specific trip, but these estimates, and variations for different travel modes and

specific conditions, provide a reasonable basis for analyzing true transport costs.

This price structure is inefficient. Vehicle owners have little incentive to limit driving to

trips in which benefits exceed total costs, resulting in economically excessive vehicle

travel that reduces transport system performance. Problems such as traffic congestion,

traffic risk, and pollution are virtually unavoidable with current pricing.

Transportation Cost and Benefit Analysis II – Executive Summary

Victoria Transport Policy Institute

(www.vtpi.org)

16 March 2011 www.vtpi.org/tca/tca00.pdf

Page ES-7

This price structure is horizontally inequitable because people must bear significant costs

imposed by others. It is vertically inequitable because it tends to benefit the wealthy and

reduces travel options for non-drivers. Whether price increases are regressive depends on

how revenues are used. Actions that increase travel options for non-drivers, such as better

transit service, improvements to the pedestrian and bicycling environment, and reduced

urban sprawl, tend to be overall progressive because they benefit disadvantaged people.

There is no single solution to our current transportation problems. Neither, improved

bicycling and walking facilities, increased public transit service, “smart” highways, nor

less polluting vehicles alone can solve our transport problems while driving is so

underpriced. More efficient pricing is essential to solving transportation problems.

Changes in planning, land use, and infrastructure investments are also needed. An

efficient and equitable transportation system offers users efficient mobility options and

incentives to use each mode for what it does best.

Conventional planning tends to evaluate transportation performance based on travel

distance, which favors mobility over accessibility, faster modes over slower modes, and

speed over comfort. For example, conventional transport economic analysis can calculate

the monetized value of travel time savings from highway expansion that increases travel

speeds, but cannot provide monetized benefits from increasing local services, improving

children’s ability to walk and cycle to schools, or from increasing the convenience and

comfort of public transit travel, for example, by providing real-time bus arrival

information or more comfortable transit stop waiting conditions.

Since most urban trips are relatively short (less than 5 miles), there is a “transportation

gap” caused by overemphasis on long-distance travel and too little attention to bicycling,

local transit, and low powered vehicles. This creates a self-fulfilling prophecy of

increased driving, automobile dependency, inequity and sprawl. Electric cars and other

alternative fuels reduce some external costs, particularly urban air pollution, noise, and

petroleum externalities, but do little to reduce other problems such as accident risk,

congestion, and parking subsidies.

Traffic impacts on community livability deserve special attention. The road system is a

valuable public asset. In addition to accommodating vehicle travel streets define a

community’s character, accommodate walking and cycling, and allow community

interactions. Motor vehicle traffic tends to degrade these functions. New urban

neighborhood design and traffic calming programs can reduce traffic impacts and return

streets to multi-function use. Implementing these improvements requires changes to

transport planning and funding practices.

More research is needed to better estimate transportation costs under various conditions

and locations. Transport equity and diversity appear to be significant values which

deserve more research. Decision-makers need better information on consumer demands,

such as the value people place on improved travel convenience and comfort. Research is

also needed to evaluate the synergistic effects of combined planning decisions.