Fillable Printable Social Cost Benefit Analysis

Fillable Printable Social Cost Benefit Analysis

Social Cost Benefit Analysis

59

Project NPV, Positive Externalities, Social Cost-Benefit Analysis

Project NPV, Positive Externalities,

Social Cost-Benefit Analysis—

The Kansas City Light Rail Project

Sudhakar Raju, Rockhurst University

Abstract

e Heartland Light Rail project represents Kansas City’s biggest infrastructural

investment in decades. e ballot initiative for the light rail project was voted down

three times until it was finally approved in November 2006. Using best estimates of

construction costs, operating expenses and federal funding, I estimate the net pres-

ent value (NPV) of the project to be negative $343 million. From a standard NPV

perspective the Kansas City light rail transit (LRT) system is unlikely to break even.

However, if the negative externalities of auto travel and the positive externalities

associated with light rail are properly accounted for in a comprehensive social cost-

benefit framework, investment in the Kansas City LRT system becomes an increas-

ingly feasible option.

Introduction

In November 2006, after several previous failed attempts, voters in Kansas City

approved a measure for the construction of a light rail transit (LRT) system that

would be partly financed by a 3/8-cent sales tax for 25 years. According to the offi-

cial ballot language, the plan proposes the construction of a new $1 billion, 27-mile

Heartland Light Rail system. e plan also proposes enlarging the light rail system’s

service area by employing a green fleet of 60 electric shuttles that would provide

connecting transit service to nearby job and shopping centers.

Journal of Public Transportation, Vol. 11, No. 4, 2008

60

Kansas City and Transportation

During the 1990s, Kansas City embarked on a widespread strategic planning ini-

tiative. A key recommendation of the initiative involved the city’s transportation

system. Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) data indicated that the poor

quality of Kansas City roads imposed annual vehicle operation costs of $651 on

Kansas City drivers

1

—the highest in the nation’s major cities outside California.

Data from the 2003 national Consumer Expenditure Survey indicated that among

major metropolitan areas, Kansas City residents spent about 20 percent of their

budget on transportation—the fifth highest in the nation. Kansas City offers no

real alternatives to driving and, with continued growth, transportation is pro-

jected to become even more time-consuming and costly. As a result, a key recom-

mendation of the planning initiative was for the development of a light rail transit

system to “enhance the movement of people, to protect clean air, and to protect

the natural environment … and the promotion of more clustered development

along transit corridors.”

2

Kansas City is actually composed of two cities—Kansas City, Missouri and Kansas

City, Kansas. Kansas City, Missouri is, by itself, the largest city in Missouri. e com-

bined population of the greater Kansas City metropolitan area is close to 2 million.

Once known primarily for agriculture and manufacturing, Kansas City today has

a diversified economic base composed of telecommunications, banking, finance,

and service-based industries. Kansas City is also a transportation hub and a major

national distribution center. Transportation is, therefore, central to the continued

development of Kansas City.

Notwithstanding the importance of transportation for Kansas City’s economic

development, recent investment in transportation infrastructure in Kansas

City has been poor. In a study conducted by the Mid-America Regional Council

(MARC), a regional public policy research organization located in Kansas City,

Kansas City ranked at the bottom of a group of peer cities in terms of public trans-

portation financing. e only public transit offered by the city is bus services. But

even this service is underinvested; in fact, Kansas City would have to double its bus

services to reach the average of its peer cities.

Due to the extensive highway projects implemented in Kansas City during the

1970s and 1980s, Kansas City possesses the most freeway lane miles per capita of

all large urbanized areas in the United States and the fourth highest total roadway

miles per person.

3

Even though Kansas City ranks high in the number of roadway

miles per person, its roads are in worse condition than national and peer city aver-

61

Project NPV, Positive Externalities, Social Cost-Benefit Analysis

ages. e Road Information Program’s (TRIP’s) 2004 Bumpy Roads Ahead report

found that Kansas City’s “poor” pavement conditions significantly exceeded

national averages, and Kansas City had a smaller percentage of roads classified as

“good.” In addition, overall pavement conditions have notably deteriorated since

2000.

Transportation by automobile is, by far, the preferred mode of transportation in

Kansas City, and recent studies indicate that reliance on automobiles is continuing

to grow. More than 93 percent of all trips are by automobile, of which 83 percent

are single-occupancy trips and 10 percent are carpool trips. About 4 percent work

from home, 1 percent walk to work, and public transit accounts for the remaining

1 percent.

e extensive roadway system in Kansas City offsets the excessive reliance on

automobiles; thus, congestion is not a major problem. However, there is significant

congestion during peak periods, and nearly all studies are in agreement that con-

gestion is growing. e 2001 Travel Time Study conducted by MARC found that

congested travel as a percentage of peak vehicle miles traveled increased from 5

percent in 1982 to 32 percent in 2002. However, this still compares very favorably

to other urban areas in which congested travel increased far more substantially,

from 24 percent in 1982 to 65 percent in 2002. e low-density urban form of Kan-

sas City means that travel distances in Kansas City are longer. e average vehicle

miles of travel (VMT) per person in Kansas City was 28.65, whereas the average for

metropolitan areas of similar size was 24.04 VMT per person each day.

4

However,

the relatively lower congestion in Kansas City results in greater travel speeds and

shorter travel times. e MARC 2001 Travel Time Study found that even though

average travel speeds steadily increased, “there are several routes where conges-

tion is an increasing problem. is is evident in that there is a large percentage of

routes and segments with delay … and several of the most highly traveled routes in

the region have significantly more delay than in previous studies.” A similar study

by the Missouri Department of Transportation found that of the 10 most heavily-

congested sections of the urban Missouri interstate highways, 7 are located in

Kansas City.

5

The Heartland Rail System

Planning for the Kansas City LRT system began in the 1990s. e Technology Work

Team considered six technology options—improved bus service, bus rapid transit

Journal of Public Transportation, Vol. 11, No. 4, 2008

62

with dedicated guideway (such as in Ottawa or Curitiba), electrified bus rapid

transit (as in Lille, France or Mexico City), electrified street car, monorail and light

rail—and settled on light rail as the preferred technology with electric bus transit

as a second option.

e Heartland Rail system would serve some of Kansas City’s densest residential

neighborhoods in the mid- and south-town areas. e proposed system align-

ment runs through downtown Kansas City, serving an employment corridor with

250,000 jobs. e primary market that would be served by the proposed light rail

system is work trips though strong connections to cultural and shopping centers

would result in a strong secondary market. During peak weekday morning and

evening periods, service is proposed to be provided every 12 minutes.

Capital Costs, Operating Costs, and Funding for the

Heartland Light Rail Project

e Heartland Rail system, as proposed, would constitute one of the biggest infra-

structural investments in Kansas City history. Detailed estimates of capital costs,

cash inflows, and cash outflows for the project is provided in the Central Business

Corridor (CBC) Transit Plan. e essential features of the project and the underly-

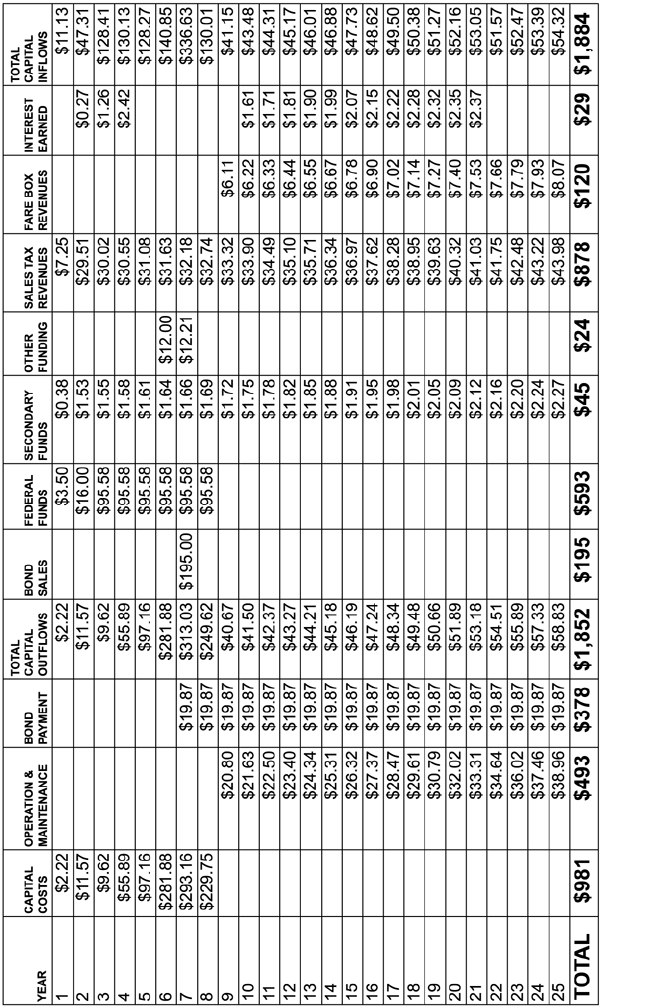

ing project assumptions of the CBC Transit plan are summarized in Table 1.

e CBC plan assumes that the project would be funded by three major sources.

Federal funding of $593 million was assumed to cover 60.50 percent of the capital

costs of the project. A 3/8-cent sales tax for 25 years was assumed to generate $29

million in the first year and a total of $878 million over the 25-year tax period. e

project would also be funded by a $195 million, 19-year, 7.70 percent bond issue,

which would result in interest payments of $19.87 million annually. e funding

for the project would become effective on April 1, 2009.

The Financial Economics of the Heartland Light Rail System—

Project Analysis

While detailed estimates of capital costs, cash inflows, and cash outflows over the

25-year life of the light rail system are provided in the Central Business Corridor

(CBC) Transit Plan, there is no attempt to provide an economic or financial analy-

sis of the project. e project inflow and outflow estimates provided by the CBC

plan over the 25-year life of the project are shown in Table 2.

63

Project NPV, Positive Externalities, Social Cost-Benefit Analysis

Table 1. Project Assumptions

Project Life 25 years

•CapitalPeriod 8years(Year1–Year8)

•OperatingPeriod 17years(Year9–Year25)

Estimated (Inflation Adjusted) Capital Costs $981

Base Estimate of Annual Operating/Maintenance Costs $15.20 million

Annual Growth in Operating/Maintenance Cost 4%

AnnualOperating/MaintenanceCostinYear9 $20.80million

($15.20 x [1 + .04]

8

= $20.80)

TotalOperationandMaintenanceCost(Years9-25) $493

Federal Capital Funding Percentage 60.50%

Secondary Funds Base Assumption $1.50 million

(Annual Growth Rate 1.80%)

Base Estimate from Sales Taxes $29 million

Estimated Annual Growth in Taxes 1.80%

Tax Period 25 years

Bond Issue $195 million

Bond Repayment Period 19 years

Bond Interest Rate 7.50%

Annual Bond Interest Payment

$19.87 million

($195 million issue, Effective rate of 7.70%, 19 years)

BaseEstimateofFareRevenue(Year9ofproject) $6.11million

Annual Growth Rate in Fare Revenues 1.80%

Journal of Public Transportation, Vol. 11, No. 4, 2008

64

Table 2. Project Cost and Revenue Flows (in millions): Estimates Based on CBC Study

Notes: Total Capital Outflows = Capital Costs + Operation & Maintenance + Bond Payment

Total Capital Inflows = Bond Sales + Federal Funds + Secondary Funds + Other Funding + Sales Tax Revenues + Fare Box Revenues +

Interest Earned

65

Project NPV, Positive Externalities, Social Cost-Benefit Analysis

A good starting point for financial analysis is to compute the NPV of the Kansas

City LRT project. For long-term capital projects, the Federal Transit Authority

(FTA) recommends using a project discount rate of 7 percent.

6

Using this as the

applicable discount rate, the NPV of the project based on the CBC Transit Plan

estimates turn out to be about $70 million. However, this NPV value is based on

preliminary estimates provided in the CBC Transit Plan and needs to be readjusted

in the light of recent developments and other factors such as inflationary effects.

e most significant revisions to the preliminary estimates are:

• eCBCTransitPlanestimatesarebasedonoperatingcostassumptionsof

$20.80 million. More realistic estimates suggest that operating costs would

probably be in the range of $25-$30 million annually. e mid-point of this

range is used here with the assumption (as in the CBC study) that operating

costs escalate annually at 4 percent.

• eCBCTransitPlanrevenueestimatesarebasedona½-centsalestax

assumption. e actual amount approved by Kansas City voters was 3/8

cents. (us, actual sales tax revenues earmarked for the project are 25

percent lower.) e lower estimate suggests that a 3/8-cent sales tax would

generate sales tax revenues of $23 million annually. e CBC estimates were

revised to reflect the lower sales tax with the assumption (as in the CBC

study) that sales tax revenues increase by 1.75 percent annually.

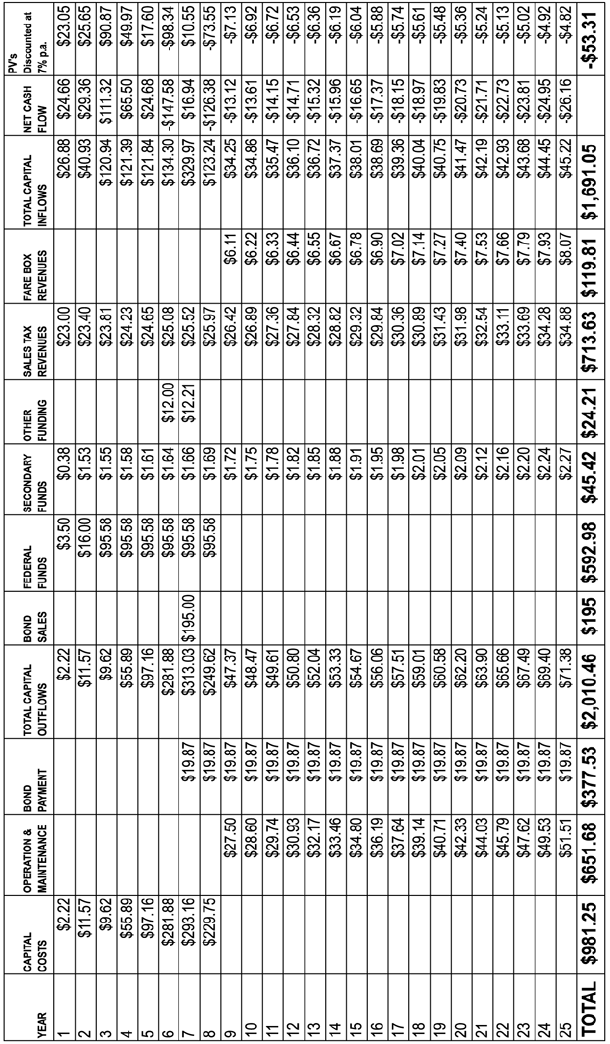

e revised estimates are shown in Table 3. e NPV of the project based on the

net cash flows of the project turn out to be -$53.31 million, while the Internal Rate

of Return (IRR) is 10.58 percent

7

—a clear signal that the project has some inherent

problems.

What is clear from an analysis of the cash flow stream is that the project is heavily-

dependent on federal funding. Ironically, the only periods in which the project has

any positive cash flow stream are the initial years—the periods when one would

expect the project to run deficits because of high capital costs. is is due to the

fairly high values assumed for federal funding. While capital costs reach a peak in

years6-8,abondissueinYear7partiallyosetssomeofthesecapitalcosts,result-

inginanetinowinYear7.

e most instructive aspect of the financial analysis is the non-self sustaining

nature of the project in the operating phase covering years 9-25. Net cash flows

in the operating phase of the project are negative in every year of the project. In

principle, the operating phase is somewhat less subject to uncertainty since the

Journal of Public Transportation, Vol. 11, No. 4, 2008

66

Table 3. Project Cost and Revenue Flows (in millions): Revised Estimates Based on CBC Study

Notes: Total Capital Outflows = Capital Costs + Operation & Maintenance + Bond Payment

Total Capital Inflows = Bond Sales + Federal Funds + Secondary Funds + Other Funding + Sales Tax Revenues + Fare Box Revenues

Net Cash flow = Total Capital Inflows - Capital Outflows

67

Project NPV, Positive Externalities, Social Cost-Benefit Analysis

major uncertainty in infrastructural projects tends to center around the substan-

tial initial investment costs. Four major factors determine the economic viability

of the Heartland Light Rail project in the operating phase of the project: operating

and maintenance costs, bond interest payments, sales tax revenues, and fare box

revenues. e effect of each of these variables are analyzed below.

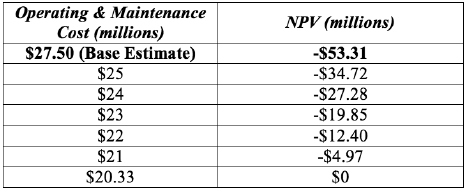

Operating and Maintenance Costs

e budgeted value for operating and maintenance cost in the first year of the K.C.

Light Rail project is $20.80 million. A more realistic estimate, taking into account

factors such as cost escalation and inflation, is $25-$30 million. Using a mid-range

estimate of operating costs, the NPV of the project, as pointed out earlier, turns

out to be negative. Now, suppose one were to give the operating costs of the

project more latitude. What is the lowest value that one could assume for base

operating costs and still end up with a positive value for NPV? Holding everything

else constant, the effect on NPV for different base year operating and maintenance

cost assumptions is reported below.

8

Table 4. Project Sensitivity to Base Year Operating &

Maintenance Cost Assumptions

us, operating and maintenance costs would have to be lower than $20.33

million at inception of project operation for NPV to be positive. Given that the

current estimate is $25 million, it seems unlikely that operating and maintenance

costs could go as low as $20.33 million. In addition, if the annual percentage

increase in operating costs were higher than 4 percent, the resulting NPV’s would

be even more unfavorable.

Bond Interest Payments

e base estimates are based on partial funding of the Heartland Light Rail Project

througha$195million,7.70percenteectiverate,19-yearbondissueinYear7of

the project. is results in interest obligations of $19.87 million over 19 years. How

low would interest obligations have to be to result in a break-even NPV?

Journal of Public Transportation, Vol. 11, No. 4, 2008

68

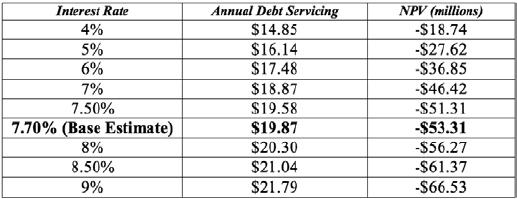

e effective interest rate assumed for the Heartland Light Rail bond issue is 7.70

percent. Of course, future interest rates are unknown, but, based on Kansas City’s

current credit rating, an interest rate of 7.70 percent seems reasonable and per-

haps even on the higher side. In 2007, Kansas City issued $138 million of general

obligation “GO series 2007A” bonds at a rate of 4.60 percent. All three credit rating

agencies—Standard and Poor’s, Moody’s, and Fitch Ratings—affirmed their belief

in the City’s financial strength. In Table 5, a19-year bond issue of $195 million is

assumed, and the effect of different interest rates and debt servicing levels on

project NPV is computed.

Table 5. Project Sensitivity to Interest Cost Assumptions

Note: e above is based on a $195 million, 19-year bond issue.

It is clear from the sensitivity analysis above that even if long-term interest rates

were to decline to a historical low of 4 percent, the resulting savings in debt servic-

ing costs is insufficient to result in a non-negative NPV. Since long-term interest

rates have historically been around 7.50 percent, it is improbable for much savings

to be realized from a decline in annual debt servicing costs alone.

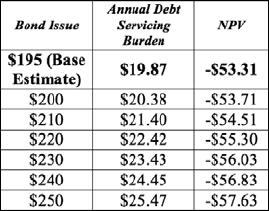

Suppose we were to consider two other options—increasing the size of the bond

issue or increasing the maturity of the issue. It is important to recognize that size,

maturity, and annual payments are all simultaneously determined, so that chang-

ing any one variable affects the value of at least one of the other variables. Now

suppose that the size of the issue was increased from $195 million to some higher

value while maturity of the issue is kept constant. What effect would this have on

the NPV of the project? e results are reported in Table 6.

Clearly, increasing the size of the bond issue worsens the NPV of the project. is

isduetothefactthatwhilealargerbondissueincreasesthecashinowinYear

7, it also results in higher debt servicing burdens in the outer years of the project.

In fact, a lower issue size may be the answer, but there may be constraints about

running unacceptably high levels of deficits in the initial years of the project.

69

Project NPV, Positive Externalities, Social Cost-Benefit Analysis

Table 6. Project Sensitivity to Bond Issue Size

Note: e above assumes an effective

funding cost of 7.70 percent and a

maturity of 19 years.

Would increasing the maturity of the bond issue and consequently reducing the

annual debt servicing burden improve the NPV of the project? Suppose the size

of the issue and interest rate remained at $195 million and 7.70 percent, but the

maturity of the issue was increased from 19 to 25 years. e annual debt servicing

burden in this case would decrease from $19.87 million to $17.80 million over the

life of the project, and NPV would improve from the base case NPV of -$53.31 mil-

lion to -$45 million.

At an extreme, imagine that Kansas City could issue a perpetual bond. Suppose

the issue size is $195 million and the interest rate is 7.70 percent. In this case, the

annuity payments would decline from the base case estimate of $19.87 million per

annum to perpetual annuity payments of $15.02 million ($195m x .0770). is is

the lowest-possible annual debt servicing burden attainable by increasing bond

maturity. However, this would still result in a negative NPV.

e bottom line is this: Declining interest rates and consequently a lower debt

burden would improve NPV, but even at very low interest rates the project does

not break even. Other solutions, such as increasing the size of the bond issue or

increasing the maturity of the bond issue, are either not helpful or do not impact

the NPV in any substantive manner.

Sales Tax Revenues

Initialestimatessuggesteda½-centsalestaxearmarkedfortheHeartlandLight

Rail project. Anti-tax sentiment is, however, very strong in Kansas City, and

the final amount approved for the light rail project by Kansas City voters was a

3/8-cent tax for 25 years. e possibility for increasing the sales tax rate is remote;