Fillable Printable Dynamic Balanced Scorecard Template

Fillable Printable Dynamic Balanced Scorecard Template

Dynamic Balanced Scorecard Template

A DYNAMIC BALANCED SCORECARD TEMPLATE

FOR PUBLIC SECTOR AGENCIES

Keith Linard, Senior Lecturer

Merilyn Bassett, Visiting Fellow

Joseph Yoon, Postgraduate Student

Lubomir Dvorsky, Postgraduate Student

University of New South Wales, (Australian Defence Force Academy)

ABSTRACT:

This paper describes a dynamic balanced scorecard template developed for the Australian

Federal Department of Communications Information Technology and the Arts (DCITA) by a

research team from the University of New South Wales and CSC(Aust) in conjunction with

senior DCITA executives and ministerial staff.

The project involved the development of a prototype management flight simulator, built

around the Kaplan and Norton 'balanced scorecard' (BSC) concept. The engine for the

simulator is a system dynamics model, built in Powersim, designed to draw real time data

from departmental information systems. The prototype was designed as a template that could

be customised for any level of the organisation.

The model is broadly structured around the traditional BSC sectors, adapted for the Australian

public sector environment. It incorporates the following sub-models:

• Resources: (human capital; outsourced services)

• Internal Process: (workflow; corporate communication)

• Customer Perspective: (service quality, corporate governance & corporate health)

• Learning & Growth: (intellectual capital; personnel development)

The paper includes illustrations of causal loop and stock flow diagrams of key components.

Keywords: system dynamics; causal loop; balanced scorecard; knowledge management;

performance management; public sector management.

PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT - AUSTRALIAN PUBLIC SECTOR CONTEXT

The Australian Public Sector has undergone a series of reforms in recent years with the aim of

providing the government of Australia with the services it requires in a rapidly changing

world. The pressure for reform has been driven by both international and domestic

developments including globalisation, technological change, policy initiatives, the changing

workplace environment and the demographics of the primary provider of services, the

Australian Public Service (APS).

The suite of financial, employment, competition and customer service reforms focuses on

developing a more business-like performance culture within the public sector. These reforms

provide the opportunity to develop a Balanced Scorecard for Australian Public Sector

agencies that assists managers to assess service delivery performance and the capacity to

adapt in a rapidly changing environment.

Federal Government Resource Management Reforms of the 1990’s

A key policy of the current government for a high performing public sector is to build a

stronger budgetary position through expenditure restraint and concentration on core business.

1

A range of the recent resource management reforms are briefly outlined below to assist in

clarifying the customer/service provider relationship that exists in the Australian federal

public sector context and which differs substantially from a public sector that primarily

provides services direct to the community.

The resource management approach implemented by the Australian Public Sector (APS) in

July 1999 consists of an outcomes, outputs, accrual based budgeting and reporting resource

management framework, supported by devolved banking and financial management systems.

The essential purpose of the outcomes and outputs framework is to answer three questions:

(i) What does government want to change? (outcomes)

(ii) How does it want to make that change? (outputs)

(iii) How does it know if it is succeeding in making that change? (indicators)

The system works as a hierarchy. Government, through its ministers and with the assistance

of relevant agencies, specifies the outcomes it is seeking to achieve in a given policy arena.

These outcomes are specified in terms of the impact government is aiming to have on some

aspect of society, the economy or the national interest. Parliament appropriates funds to allow

the government to achieve these outcomes.

These funds allow government to ‘buy’ outputs or services from agencies. Agencies specify

the outputs (eg. policy advice) they undertake to provide to contribute to the achievement of

these outcomes, including through third parties.

Specification of what will be delivered can help improve the understanding and knowledge of

those outside the agency who have an interest in its performance, including Ministers,

Parliament and external accountability bodies such as the Auditor General.

The framework encourages agencies to focus on the specific products they deliver (outputs)

and how to deliver them in the most efficient and effective ways; and to identify business

lines they should drop or outsource. The implementation of accrual accounting using

1

The Hon. John Howard, MP, Prime Minister: Launch of Ethical Standards and Values in the Australian Public

services – MAB/MIAC publication No. 19, 9 May 1996.

generally accepted accounting principles provides the basis for benchmarking comparisons so

that decisions about preferred providers are better informed.

Annex 1 illustrates the typical way a work unit might develop its work action plan, identifying

the planned outcomes and outputs, resources required and agreed, performance criteria and

other work units whose activities impinge on achievement

Where services are provided direct to industry and the community, the development of client

service charters is an integral part of the reforms and an important indicator of performance.

The Government itself makes decisions on programs and (usually) on guidelines for service

provision. Within these guidelines, however, governments expect service delivery to be of a

high standard and public servants are accountable to their Minister and to government for

their service to customers in this context.

Charters must specify standards for service delivery and set out complaint handling and

feedback mechanisms, and must be developed through consultation with customers and staff.

Agencies are required to report annually, through the Department of Finance and

Administration, to the Parliament on their performance against the charter.

The reforms outlined above provide a more complex view of the customer perspective for the

Australian national public sector then that which exists in the private sector. In the public

sector context, the prime customer (ie the agent who pays for a reciprocal service) is the

Minister on behalf of the Government.

CHARACTERISTICS OF AN AUSTRALIAN GOVERNMENT BSC

The ‘Customers’ of the Federal Public Sector

Much of the writings on implementing the Balanced Scorecard in the public sector focuses on

levels of Government that provide services direct to the community. However, in Australia,

community services are primarily the responsibility of State and Local Governments. As

noted above, the primary function of the Australian Federal Public Sector is to provide a

range of services to the Government through the Minister responsible for the function.

Departments also have a legal requirements which set up ‘customer relationships’, especially

to the Auditor General and to the Parliament in respect of ‘governance’.

In those cases where Federal Departments do provide services direct to the public, they are

required to prepare and implement a service charter, providing a clear ‘customer relationship’.

Thus there are three ‘Customers’ who may need to be addressed in a BSC:

• for most departmental activities, the Minister, and through him/her, the Government;

• in respect of governance, the Auditor General and Parliament, as well as the Minister;

• for service delivery activities, the corporate or individual service recipients.

The BSC template that has been developed focuses specifically on the relationship between

managerial responses to any ‘workload-resourcing’ gap (the ‘Capacity Gap’), and how this

impacts on the first two ‘Customers’ above. The model outputs relate specifically to output

quality index; probability of fraud / probity incident; and probability of EEO incident.

The following causal loop diagrams illustrate the mechanisms by which these are impacted by

departmental operations. The interrelationships between the respective work area outputs and

their impact on achievement of outcome indicators is subject of a separate study.

Resources Performance Management in the Federal Public Sector

Over 90% of Federal Government CEOs consider financial results to be one of the top three

indicators of their organisation’s success. However, financial management in these agencies

differs dramatically from the private sector context in that the revenue side of the budget is a

given, and the focus is simply on effective and efficient management of the expenditure.

The quantum of funds made available to a Minister to implement Government programs is the

end result of a complex interplay of macro-economic deliberations, ministerial bargaining and

political judgement. Issues regarding what can be delivered (in terms of quality and quantity)

for the proposed funds are significant inputs. But such relationships are largely

approximations. Lack of skilled management (for example as a result of high turnover or

overwork) can result in errors in estimating required workload.

When the Government has determined its policy, the bureaucracy has only minor leeway in

changing the quantum or time schedule of the service. In addition, a variety of unplanned

business pressures inevitably impact on planned business. Unforeseen events such as fraud

within the Department, a by-election in a sensitive electorate, or a major controversy relating

to the Minister’s policy responsibility inevitably generate workload which is expected to be

‘absorbed’. The resource management task is to deliver the planned outputs within budget.

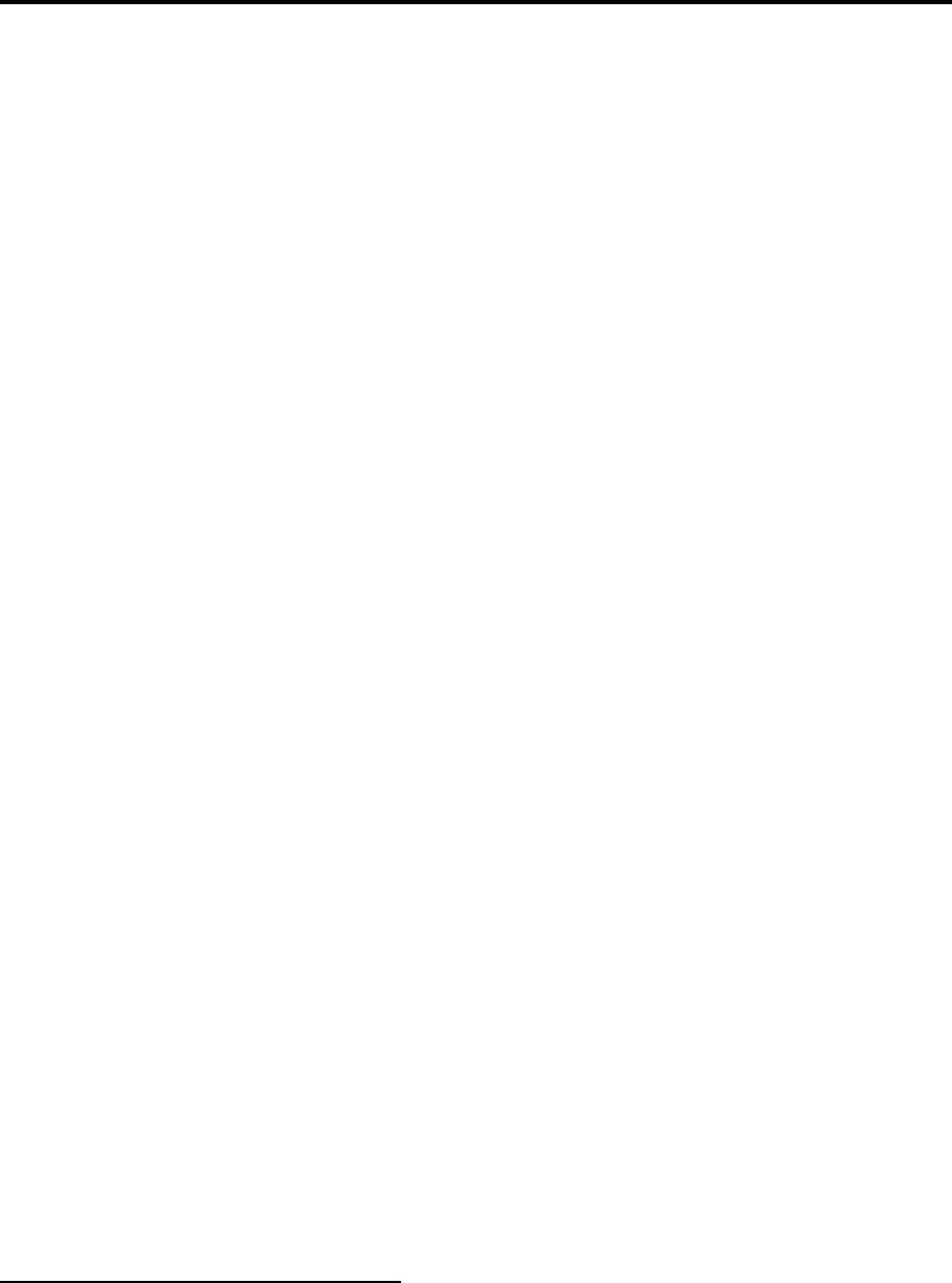

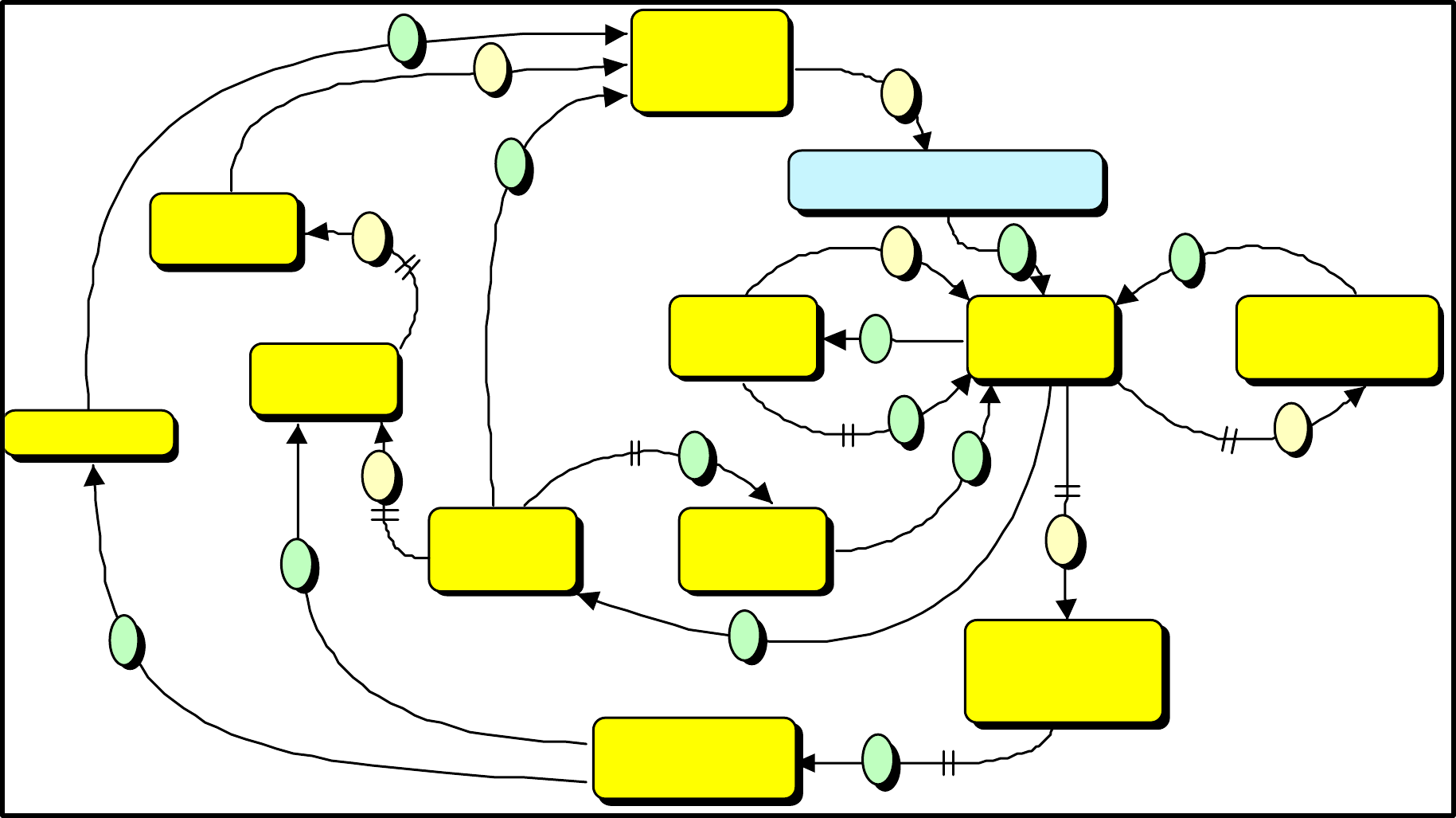

Figure 1 illustrates interrelationships in the resource sector. ‘Customer Demand’ represents

the Government’s (through the Minister) expectations which also determines the resourcing

level. It is almost axiomatic that available resources will be less than that required for quality

implementation of all the planned workload, let alone the inevitable unplanned demands.

Whether the management response to any ‘capacity gap’ is innovative or dysfunctional is a

function of the organisational competencies, which in turn is the result of leadership and

investment in capability, the latter balancing short term impacts on recurrent resources.

Figure 1: Key Resource Sector Interdependencies in Federal Departments

Department

Resources

s

Annual

Workload

Planned

Recurrent

Resources

Customer

Demand

s

o

o

Business

Planning

Errors

s

s

s

s

s

s

o

s

s

'New'

Business

Base Load

Business

Total

Effective

Capacity

Capability

Investment

CAPACITY GAP

o

Management

Effectiveness

Dysfunctional

Responses to

Gap

Innovative

Responses to

Gap

o

s

s

s

Learning Organisation

Competencies

s

o

s

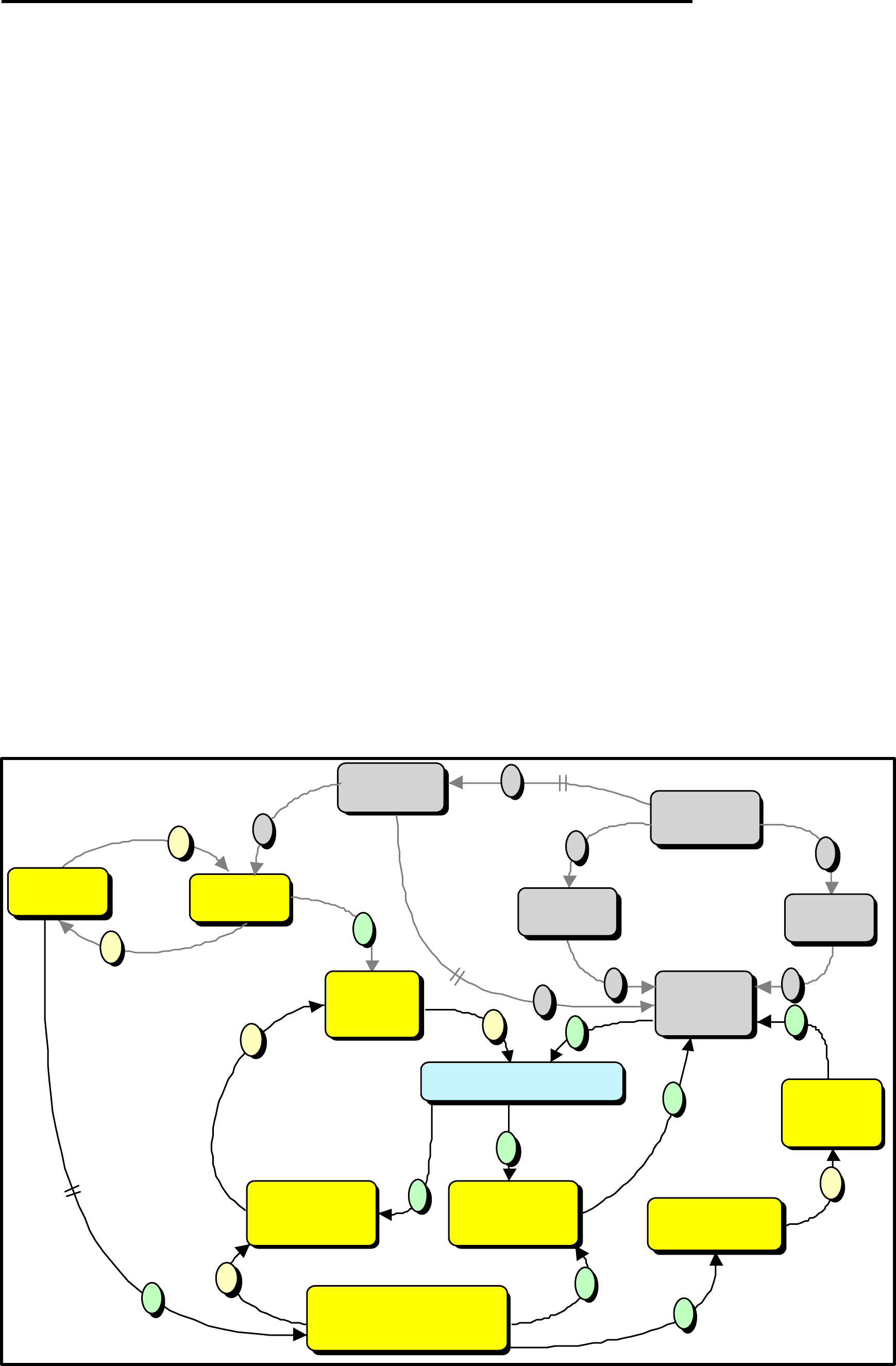

s

Figure 2 depicts the staffing module of the Resources Sector in the Dynamic BSC model.

This model tracks skill levels of senior executives, executives, technical and administrative

support staff, based on staff turnover rates and time at each level to reach full efficiency.

Figure 2: Staff Resources Segment of Dynamic Balanced Scorecard Model

At the moment this is a relatively simple model, but the intention is, at a later stage, to

incorporate the human capital accounting concepts of Paul Straussmann and Eric Sveiby.

Key resource management performance criteria relate to corporate governance (probity, fraud

control, etc), managing expenditure patterns (and especially employment related expenditure

patterns) to budget and achieving efficiencies in an increasingly efficient environment.

The Characteristics of the Internal Processes in the Federal Public Sector

The core processes in a Federal Department are essentially the same as for the private sector.

These are to:

• Establish direction;

• Acquire resources;

• Provide capability; and

• Execute the mission.

Whilst the Government establishes the policy and program outcomes that are to be achieved

in exchange for the financial resources, management translates the vision and allocates the

capabilities to achieve the delivery of agreed outputs.

The resource management framework provides a backdrop for an integrated planning process

that links corporate plans, business plans and individual plans. This planning process focuses

on achieving results through the delivery of outputs as the agency, the business unit and the

individual’s performance is linked to the outputs which in turn is linked to the outcomes that

the Government’s desires for the community. (Refer Annex 1).

As noted in relation to resource management, once the budget framework is set, Federal

Departmental managers have limited scope for obtaining extra resources. Any increase in

workload, or workload underestimate, typically will be addressed by working harder :

Personnel

Resources

Return To

Model

Sector

progress1

progress3 progress4

NovAttRate

SkilledAttRate

departing_

CompAttRate

progress2

TraiAttRate

hiring_SupStaff

Progress_delay Progress_delay Progress_delay Progress_delay Attriton_Rate

NoviceAttRate TrainAttRate_2 CompAttRate_1 SkilledAttRate_1

hiring_ExecStaff

Novice_ Trained_ Competent__ Skilled_ Experts

Support_Staff_Need

InitTrained

InitCompetent

InitSkilled InitExpertInitNovice

Executive_Staff_Need

! !

!

!

• more intense and longer hours of work (unpaid overtime)

• reduction in time devoted to training and development

• reduction in strategic management activities (through redirection of 'management

time' to 'task time')

• deferring some work (which simply postpones the day of reckoning) and

• reduction in target quality of inputs (e.g. through cutting background research effort)

or outputs

As illustrated in Figure 3, if such responses are prolonged, they tend to bring about

dysfunctional feedback effects which eventually increase the capacity gap, through increased

re-work, falling moral, increased staff turnover.

Where there is excellence in leadership and a culture characterised by the ‘learning

organisation’ one could expect innovative responses to any significant or prolonged ‘capacity

gap’. In essence such innovation changes the ‘rules of the game’ and achieves the end result

much more efficiently. There are many local examples of such behaviour across the

bureaucracy, but at this juncture the authors would be sparing in their application of ‘learning

organisation’ to Departments as a whole.

Only dysfunctional responses, as illustrated in Figure 3, have been incorporated in to the

model at this stage because of lack of data to permit modelling of the ‘learning organisation’

response.

Figure 3: Key Interrelationships Impacting on Internal Processes

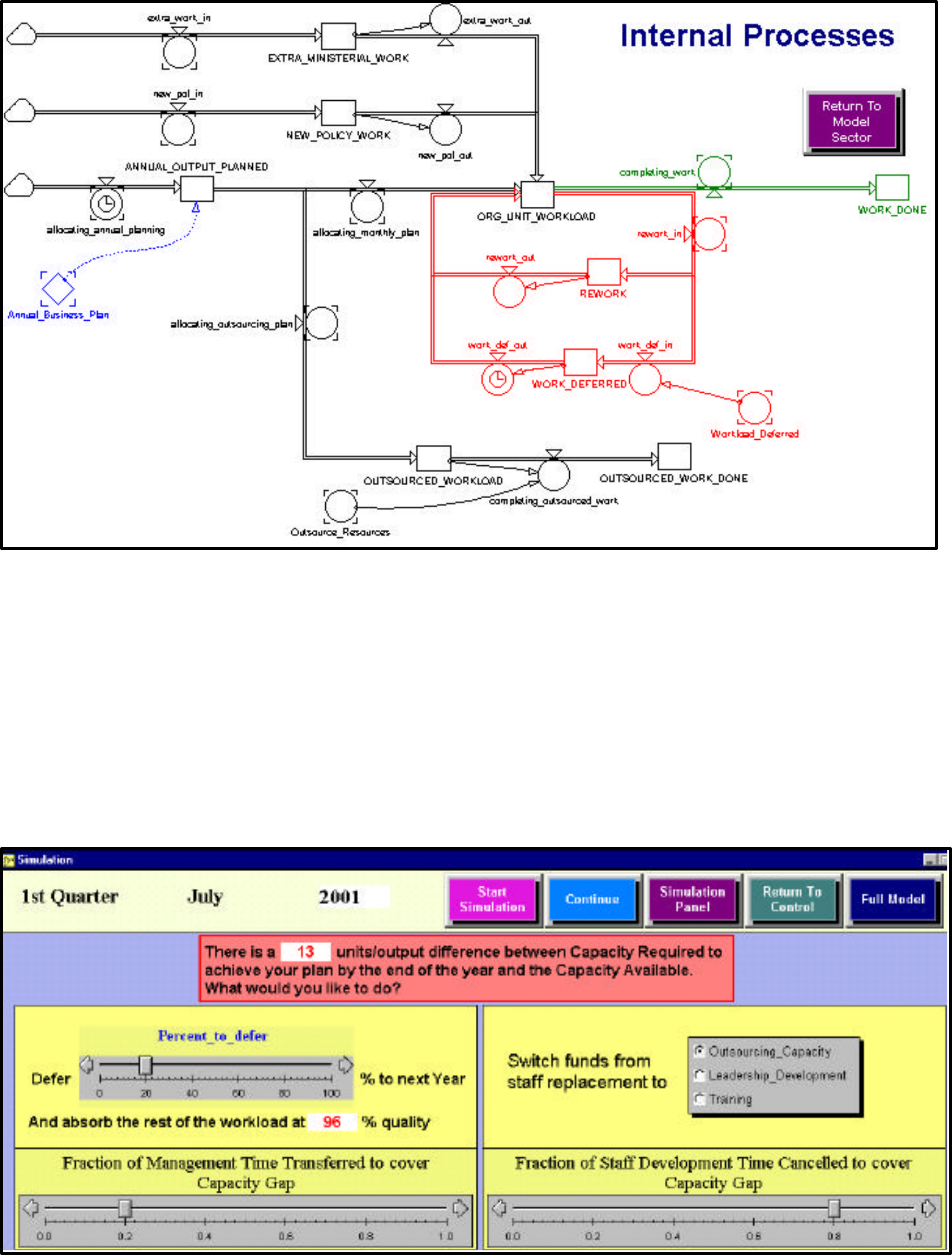

Figure 4 is a simplified extract of the Powersim dynamic BSC model relating to the Internal

Process Sector, corresponding to the causal loop diagram above. The module currently draws

its base data from spreadsheet, including:

• annual work plans

• new policy and extra ministerial projects

Staff

Turnover

s

s

o

s

s

o

o

s

s

s

s

Work

Deferred

o

s

s

Time on

Strategic

Management

Work

Intensity

Total

Effective

Capacity

Re-work /

Errors

Average

Workload

CAPACITY GAP

s

o

Management

Effectiveness

Target Output

Quality

Staff

Morale

o

o

s

Productivity

• average monthly patterns of work

The model also includes allows for outsourcing activities ( not included in the causal loop

diagram).

Figure 4: Internal Process Sector of the Dynamic BSC Model

In the model, how the capacity gap is addressed is a matter, each three months, for user

decision, with the user being given the choice of:

• specifying a % of the excess workload to defer to the next year

• switching a % of strategic management time onto the excess workload

• switching a % of staff development time on to the excess workload

• absorbing the excess workload through reduction in output quality

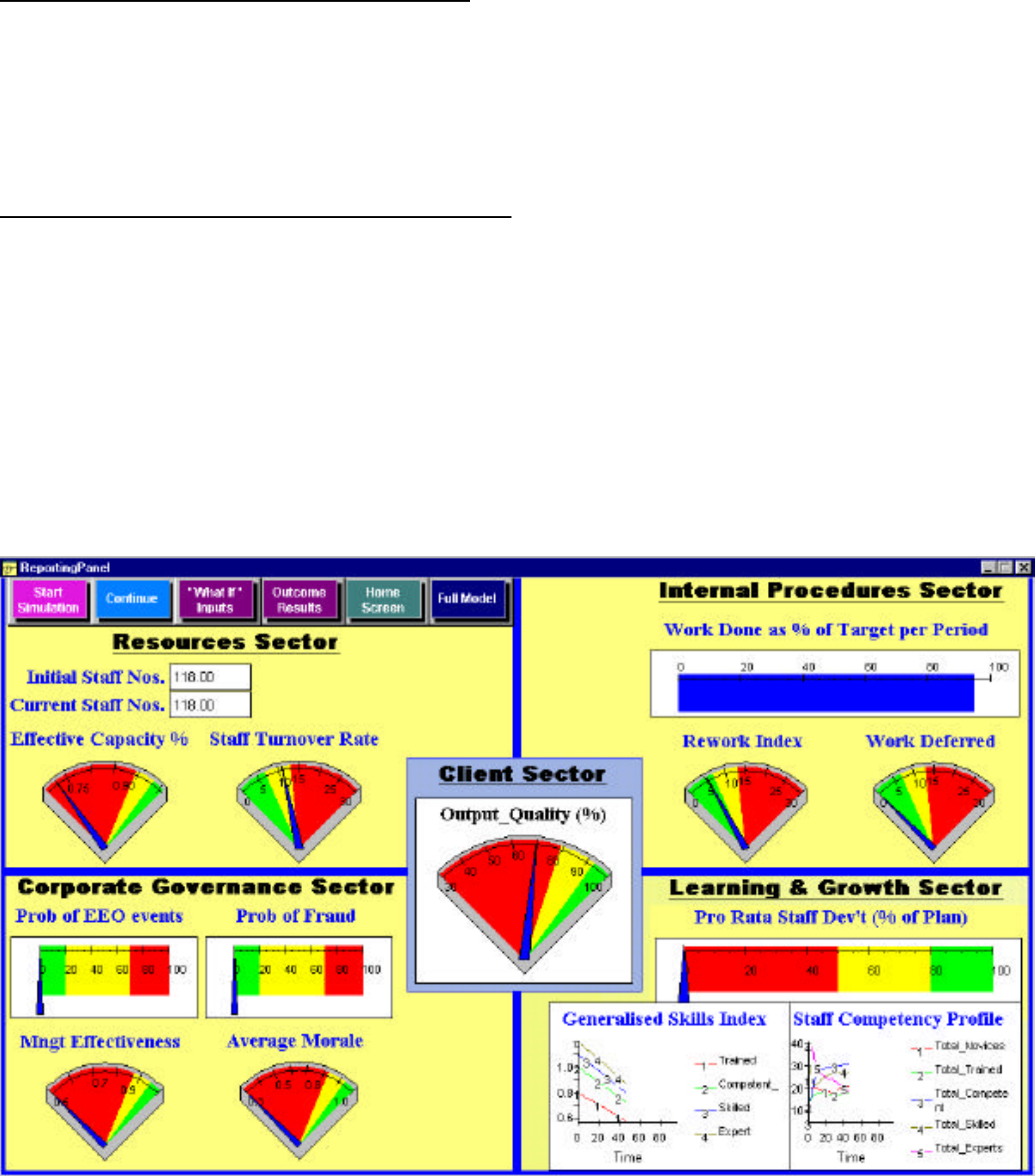

Figure 5: Dynamic BSC Simulator Control Panel

Innovation and Learning in the Federal Public Sector

Recruitment standards to the Australian Federal Public Service are high. Almost 50% of all

recruits have a Bachelor Degree or higher. Staff receive support to upgrade qualifications.

Middle & senior management training has a high priority. At the same time, work pressure

on all staff, and unpaid overtime, has increased significantly over the past 15 years. This acts

as an impediment to self-development. Also, in the face of work pressures, informal and

formal staff development tend to be among the first areas to be constrained. Figure 6 shows

the key causal relationships impacting on the learning and growth sector.

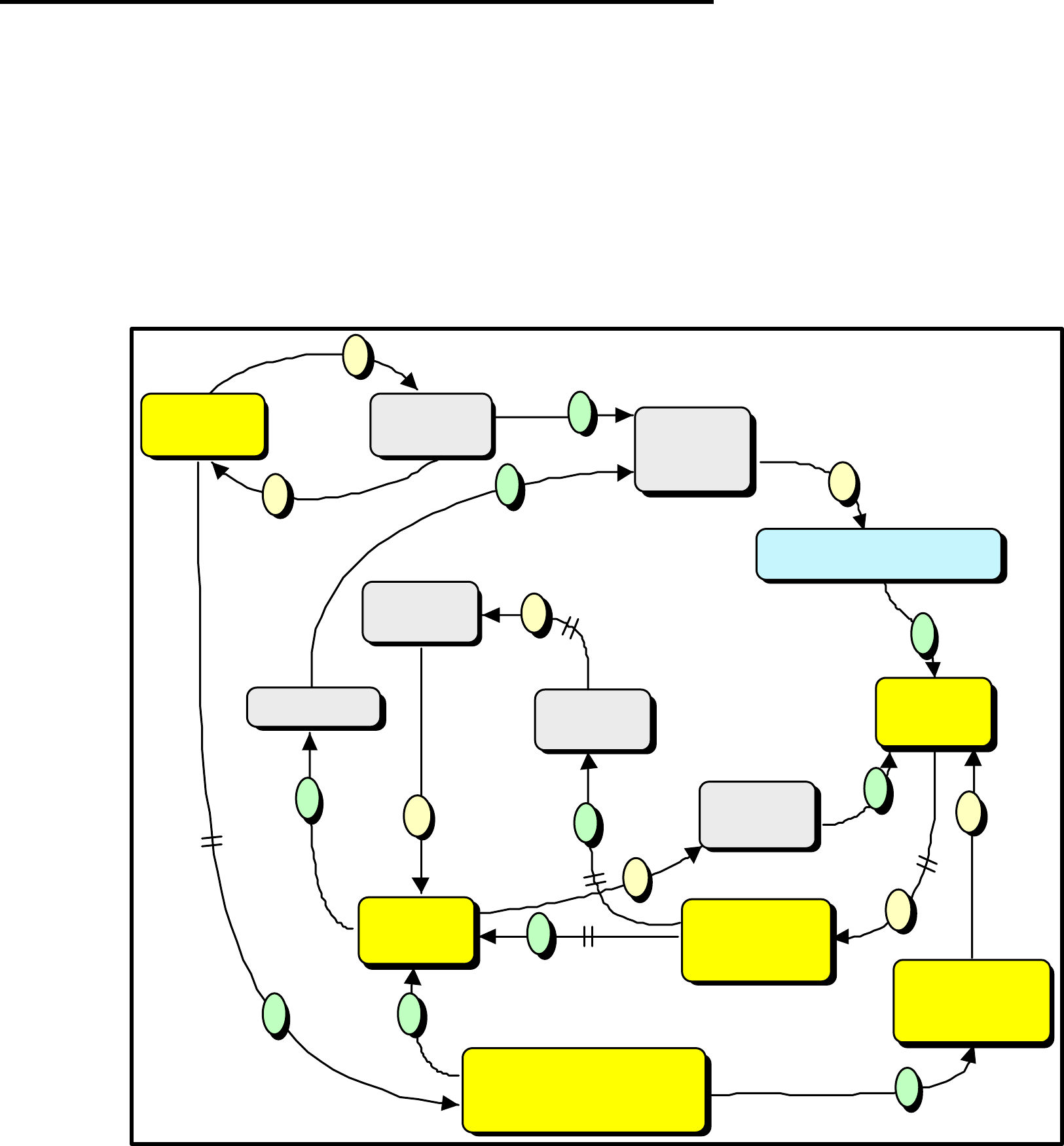

Figure 6: Key Interrelationships Impacting on Learning & Growth

In an increasingly competitive global environment, the Government’s vision for the public

service is one that has good leadership capabilities at all levels. In his address A High

Performance Public Service in August 1998, Dr David Kemp, Minister Assisting the Prime

Minister for the Public Service, stressed that strong leadership was critical to securing the

outcomes desired by Government. “Committed, robust public sector leadership is crucial to

making the most of the new framework for the Public Service. Success in this new

environment requires leaders who can establish a shared vision and sense of purpose, and

inspire, coach and enable their achievements”.

This leadership focus is important in considering the critical assumption in the model as it

now stands, that responses to a ‘capacity gap’ tend to be dysfunctional. The model, as it

stands, reflects the general experience across a wide range of Government Departments. The

case of the Federal Finance Ministry which had an average staff turnover at the executive and

senior executive levels of almost 30% per annum, and over 21% per annum across all staff,

over a 10 year period is perhaps the most striking. However, shining examples of innovative

‘Gordian Knot’ responses demonstrate the need for further research in this area.

Staff

Turnover

s

o

s

Total

Effective

Capacity

Average

Workload

CAPACITY GAP

Staff

Morale

o

Productivity

o

s

s

o

o

Skill

Level

Time for

Staff

Development

Capability

Investment

Innovative

Responses to

Gap

Learning Organisation

Competencies

s

s

s

Recurrent

Resources

o

o

s

s

o

s

Re-work /

Errors

Corporate Governance & Corporate Health

We have been undecided whether corporate governance and corporate health should be

regarded as sectors in their own right of the Federal Public Sector Balanced Scorecard. On

the one hand, Corporate Governance might be viewed as a key indicator in the Customer

Sector, whilst Corporate Health might be an indicator for the Internal Process Sector. On the

other hand, failures in these areas tend to have major political implications for the Minister

and the Government as well as significant feedback interrelationships with the other sectors.

This suggests that they might appropriately be considered as sectors in their own right. A

firm decision has yet to be made in this regard.

The Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) defines corporate governance to encompass

authority, accountability, stewardship, leadership, direction and control.

2

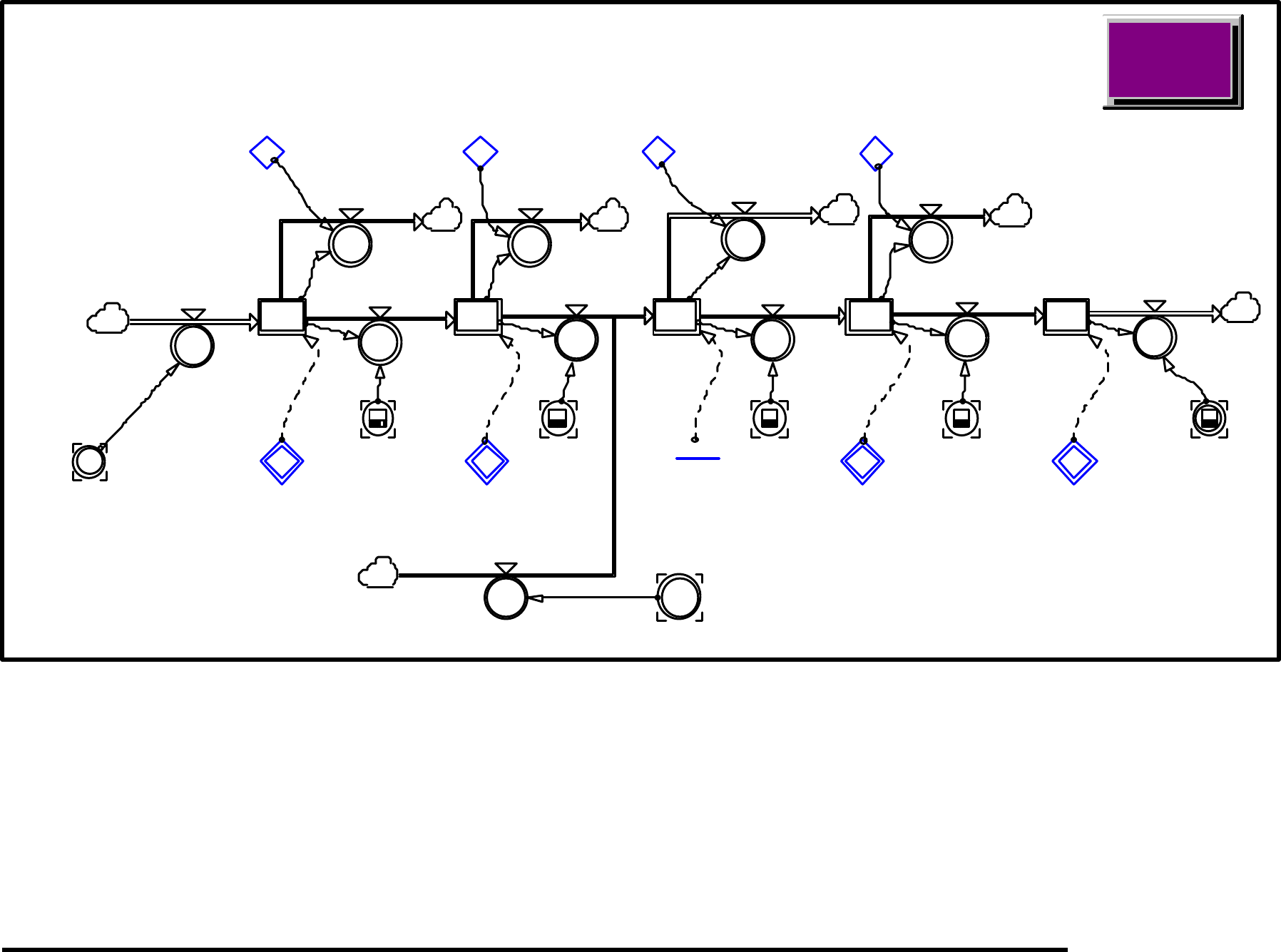

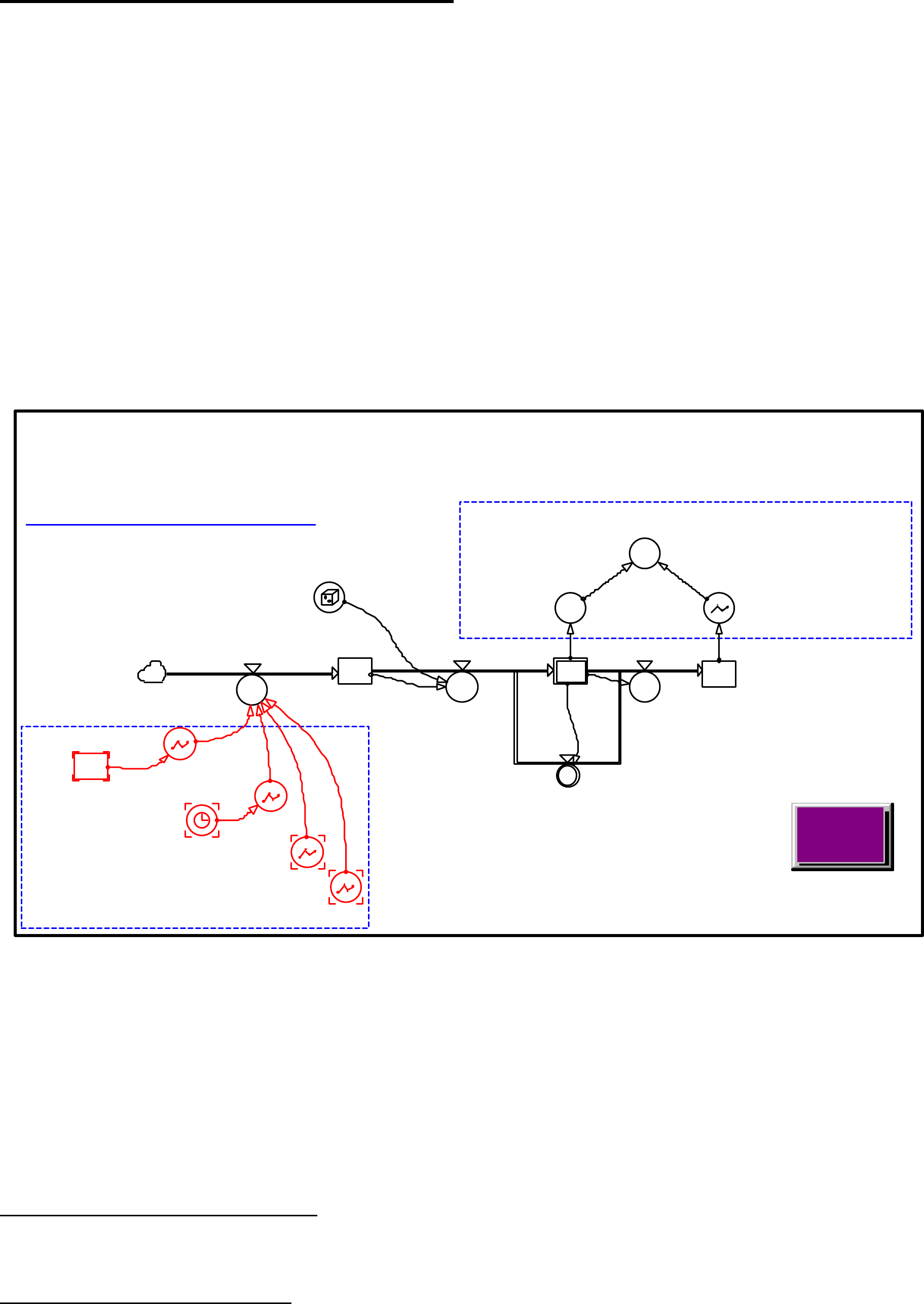

The dynamics BSC

model, at this stage, uses fraud events as a general surrogate for the effectiveness of

governance across the broad range of departmental activities.

Figure 7: Corporate Governance Sector of Dynamic Balanced Scorecard

Model Output

At the time of writing this paper, only illustrative reporting screens have been developed.

Figure 8 is an example. It is apparent from discussions with departmental staff that ultimate

use of the simulator will depend as much as anything on the “look and feel” of the output

screens. The current version of Powersim has limited flexibility in screen design and it is

likely that custom screens will be developed in Visual Basic or C++.

Future Developments

Model Validation & Verification

Whilst basic validation has been carried out during model construction, a wide range of

parameter values at this stage are simply based on the judgement of experienced public

2

ANAO, Applying the Principles and Practice of Corporate Governance in Budget Funded Agencies, Australian

Government Publishing Service, Canberra 1997.

Corporate Governance Sector

Fraudulent and Dubious Practices

Public Awareness of Fraud

Return To

Model

Sector

Internal Factors Impacting on Fraud

Fraud_Accumulating

in_progress

Fraud_occuring

Random_Num

FRAUD_TOTAL

FRAUD_EVENTPROBABILITY_OF_FRAUD

Fraud_Events_MAvg

Public_Awareness_of_Fraud

Effect_of_Fraud_Total_on_Awareness

Effect_of_Fraud_Total_on_Awareness

Management_Effectivness

Effect_of_Morale_on_Fraud

MORALE

Effect_of_StaffDevelopment_on_Fraud

StaffDevelopment_Index

Increase_in_Fraud_Prob

! !!!

service officials. Analyses will be undertaken to identify the model’s sensitivity to such

parameters and the more significant ones will be subject to more detailed research. At the

same time a very wide range of management literature is being reviewed to provide as much

support as possible for the key relationships.

Integration With Departmental Work Plans

The next stage of the project will involve a detailed strategic planning session with senior

managers to identify branch activities, outputs and performance indicators. The template at

Annex 1 was developed to guide discussion. Following this a high level model will be

developed relating the work inputs and key output indicators. This would then be integrated

with the output quality driver from this model.

Integration With Balanced Scorecard Software

The final stage of this project will be to link the dynamic simulator with the Department’s

proposed enterprise information system. At this stage no firm decision on the software has

been made : contenders include SAP, PeopleSoft and CorVu. The model design is such that it

should be relatively straight forward to draw base data directly from the corporate system.

____________________________________________

Figure 8: Illustrative Output Screen for the Dynamic Balanced Scorecard

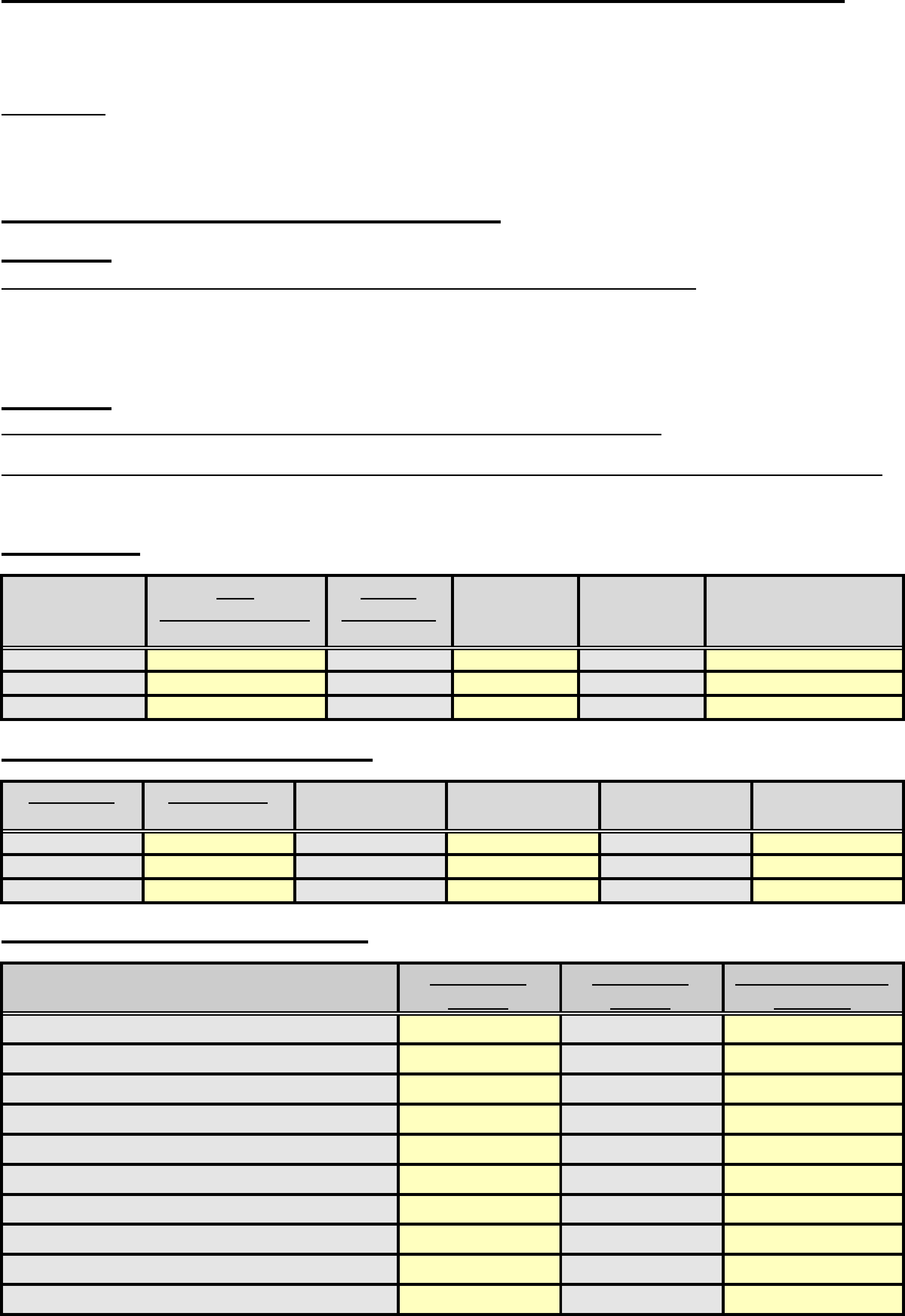

ANNEX A: 2000-01 Business Planning Development Template

OUTCOMES CONTRIBUTING TO STRATEGIC DIRECTION:

Include those outcomes that the business unit contributes to: eg.

Outcome 1 – A cultural environment that enriches the lives of all Australians)

Outcomes 2 – A competitive and diverse communications and information technology

industries and services

OUTPUTS CONTRIBUTING TO OUTCOMES:

Outcome 1

Include those outputs that the business unit contributes to outcome 1 eg.

Output 1.1 - Advice on the policy and regulatory framework for cultural heritage

Output 1.2 - Programs which support national organisations of cultural excellence

Outcome 2

Include those outputs that the business unit contributes to outcome 2

Output 2.1 – Advice on the policy and regulatory framework for communications industries

Output 2.4 – Administer departmental programs to promote access to communication services

OUTPUT 1.1

STRATEGIC

OBJECTIVE

KEY

STAKEHOLDER

CORE

PROCESS

PROJECT

/ ISSUE

ACTION

ITEM

LINKAGE TO

OTHER

BUSINESS UNIT/S

PERFORMANCE MEASURES 1.1

QUALITY QUANTITY TIMLINESS COST PRICE STAFF

YEARS

RESOURCES FOR OUTCOME 1:

DEPARTMENTAL EXPENSES OUTPUT 1

($’000)

OUTPUT 2

($’000)

Total for outcome

1 ($’000)

Employee expenses

Supplier expenses

Other operating expenses

Capital expenses

Own sourced revenue

Administered Expenses:

Subsidies

Grants

Other

Independent revenues/other revenues